Suffering Is Good For You

Suffering isn’t just pain—it’s the raw fuel that sparks both personal and collective revolution.

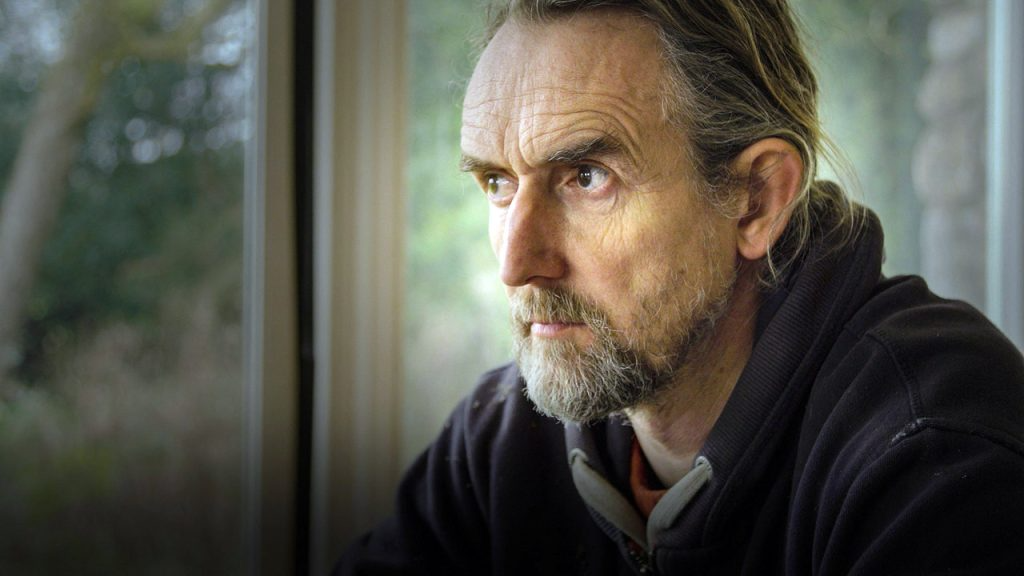

In this episode of The Spirit Of Revolution, I explore the deep and often confusing relationship between suffering, resilience, and transformation. We live in a world where the rational, calm approach to life doesn’t seem to be working – in fact, it’s taking us to the edge. So, what happens when we embrace vulnerability instead of avoiding it? How can suffering, something most of us wish to escape, actually become a source of strength?

I reflect on the paradox that lies at the heart of the struggle for change: suffering, when confronted with humility and empathy, can lead not only to personal transcendence but to collective power. Whether it’s the resilience found in the aftermath of conflict, or the strength that emerges when we face the suffering of others, there’s more at play than we might realise.

This podcast dives into how the very vulnerability we seek to avoid is the key to true revolution, both within ourselves and in the world around us. Join me in unpacking the lessons hidden in pain, and how they can fuel the fire for a transformative change that will carry us into a new world.

Listen on Spotify, Apple, Soundcloud or wherever you get your podcasts. We've worked to improve the prison phone sound quality and each episode will come with a newsletter transcript and video version on Youtube for reading along.

Transcript of Episode 6: Suffering Is Good For You

Suffering is good for you. There, I’ve said it—and I’ve just looked out of my cell window, and the sky hasn’t fallen in. Throughout this podcast, we’ll be checking regularly to see if the sky has indeed come crashing down. Suffering undoubtedly changes us, both morally and metaphysically; we either choose to see the world in new ways, or we’re compelled to.

I recall reading a biography of Winston Churchill. In case you didn’t know, for better or worse, he wasn’t a Christian. He was a true realist, with his feet firmly on the ground, unimpressed by the "God stuff." However, his life brought him close to death several times, one of which was a moment stranded in a desert with no water. It was then that he prayed to God. When we suffer, our strictly rational views tend to soften, and the non-rational can come to the fore. The experience of suffering changes us—often, though not always, for the better. As Nietzsche famously said, “What does not kill you makes you stronger.”

To explore all this, we’ll broadly use the same approach as in previous discussions: using rationality against itself to uncover its core contradictions, particularly the clash between empirical observation and the rationalist ideology of reductive materialism, the idea that “the real is just real.” Suffering, according to this ideology, is simply bad—nice and simple. In this view, self-interest is the point: we exist to avoid pain and pursue pleasure. If only it were that simple.

The counter to this received dogma is what modern psychology calls post-traumatic growth. The experience of suffering often leads to positive developments. While we could reduce this idea to “the creation of more happiness,” there’s more going on here than a simple formula of “A causes B.”

What I mean by this is that the suffering, the experience of it that we observe, involves a complex of feelings that feed in and out of each other. A significant part of this system is what we might call vulnerability: the self experiences a sense of weakness. It can no longer pretend that it can defend itself on its own; it needs the other. It is no longer so big-headed—pride comes before a fall and all that. This, then, can lead to a new humility: I am not all I thought I was, all I was made out to be. This, in turn, can lead to a sociability and openness to those around us, and a new empathy. This has happened to me—how terrible that this, or worse, is happening to others. I feel your pain. This is unlikely to sound authentic if you have not felt that pain yourself, and so this leads to a new maturity, a desire for authenticity, more interpersonal truth-telling, a lower tolerance for bullshit. These dynamics are by no means exhaustive, but they indicate that post-traumatic growth is a real thing: it exists, it’s out there, and there are reasons for it. And it creates a resilience. We are socialised into suffering; it’s something that we can learn to deal with. We are, therefore, less likely to have the double suffering of suffering about our suffering. It is what it is. Self-pity, in contrast, we might say, is the outcome of innocence—an innocence protected by privilege, of not having to deal with the world as it is. Certainly, you can see a contrast here between the more resilient poor and the more vulnerable rich, meaning those to whom nothing really bad has yet happened. It reverses the materialist view of the rich and the poor. The rigid materialist might be tempted to say, “Okay, I've lost the battle on this one,” but he still insists that he has won the war in the sense that he can go, “Okay, I accept the empirics: bad things happen, people toughen up, and so they get less vulnerable and so more happy.” We are still, then, in this world of a set cost and a set benefit, A is A, B is B, A causes B; we are still effectively talking like we are part of a car engine, a rational, logical thing. But the actual reality we experience fits a lot more easily into a more mysterious, paradoxical explanation.

The paradox is that this vulnerability itself creates resilience, set within an ecology of humility and empathy. It is by living in and being with vulnerability that these positive outcomes are made authentic and sustained. Vulnerability then becomes a weakness and a strength at the same time, or to put it another way, it is a strength because it is a weakness. We find ourselves in another world here—a world of the spirit. It plays by different rules, like those quarks and waves for the physicists. It doesn’t lend itself to a neat causal situation; everything is already there all at the same time.

I discussed this a while ago with a good friend of mine. I think it would be reasonable to say that we are both very resilient—at least outwardly. For decades, we have taken knocks as resistors and revolutionaries; we get attacked, humiliated, misrepresented, but we get up and get on with another day. As we talked, we realised that, if we’re honest, this is not because we don’t feel vulnerable, but rather because we do feel the pain of the world and the pain when the world attacks us. It’s not that we don’t feel it; it’s more that we have a knack of consciously transcending it. We look at it and move around it. We know we have been there before, and we know we will be there again. I personally often think I outwardly appear to be resilient, but there is really no guarantee that tomorrow I will not collapse into a heap of exhaustion and self-pity.

The paradox, then, is that resilience, such as it is, comes through the feeling of vulnerability, not by not feeling it. There is a notion here of what is being called "conscious incompetence," which we’ll discuss more in future episodes: you know where you want to be—fully competent—but you continually fall short on your progress to this "unconscious competence," where you have arrived and you don’t need to think about it all anymore. Thinking like this, of course, is another classic linear progression routine, which gets imposed on an instinctively subtle and mysterious process. You don’t “get there,” “arrive,” “job done”—that is the opposite of the spirit; it is the stuff of factory production. We are in a different paradigm of meaning here. The highest point is, in fact, the suspended, oscillating point—the bobbing around in the conscious incompetence realm. That’s it: getting to the top actually means you are, in that moment, back on the way down once you’ve got there and think it has arrived.

You are back to pride before a fall. None of the language here is precise—not because I'm being sloppy, but because we are grasping at processes that cannot be reduced to words. We are back, then, to forgetting a sense. We are dealing with this new, non-rational world that the experience of suffering opens up, and maybe this is why part of us is strangely attracted to suffering: because it's a means to give us meaning. In a strange sense, it makes us feel more alive.

In saying this, I don't in any way want to belittle the reality of raw horror that suffering is for so many people so much of the time. But the fact of the matter is, that is not all that is going on. There is something about the drama of life that many people feel attracted to, like the moth to the flame, as you might say. We probably all know people who seem to carry drama around with them; you cannot help feeling that if there was not a crisis going on for them, they really wouldn't know what to do with themselves. I've spoken with people who have said that they find their depression delicious, because there is something addictive about the confrontation of the self against the self. The self-destructiveness feels like a form of authenticity.

In prison, and when I work with working-class people, there are some who swear in every sentence. The world of their existence is one of continuous struggle and ragefulness; swearing is like an outlet for this, reinforcing turmoil which at the same time gives meaning and identity. It's a complicated business once you observe exactly what is going on. The most extreme thing is, I think, the paradox of armed resistance. Albert Camus, the editor of the main resistance paper in France under the Nazi occupation, talked about the extreme aliveness of not knowing if you're going to be killed from one week to the next.

It is easy, of course, to think that we have moved on beyond all this—that we are now calm and sensible and rational. But so often, this is really a function of a context rather than our personal togetherness. The unconscious competence we talked about earlier is really not about our peak performance but just where people are at before some major shit hits them. The supposed competence collapses like a house of cards. My best friend at school became very religious, studied ethics and all the rest of it; he was all calm and sorted, and then he was teaching in a school and another person purposely got him pushed out of his position. He found himself uncontrollably hateful towards that person. He was shocked by himself; he thought, I suppose, that he'd moved beyond suffering, but that was not the case. All that had happened was that he thought he had—which is something very different.

Of course, our calm, rational self-image is really a vulnerability waiting to be exposed. We don't need something external to us to shake up this vulnerable calm; life is not static, it is not outside time, it has a beginning and it has an end. There is the suffering that comes from the increasing sense of our mortality—it is always there, and it increases each year as we get older. Again, this experience is full of paradox, for reasons not so different from what we have already discussed. The awareness of an endpoint is an undeniable form of suffering, and at the same time, it opens up another variant of post-traumatic growth: we experience this mortality, and as a result, we turn towards service, towards the other, in the time that we have left. Again, this does not always happen, but it undeniably occurs for many people. There is a shift from seeing the world to seeing this world—that is, this world is not everything there is; it is a thing within an infinite void—all the time before our life and all the time after our life. There's a growing sense of the eternity beyond all this. We don't really know what this means, but it's as if we've been given the gift of a structural transcendence, in that we can lose our attachment to this world more easily—all its stuff, all this status; it starts to seem so meaningless. What opens up to us is a world beyond this time and space, a function of our spirit rather than a function of being part of a car engine, which it increasingly seems obvious we are not.

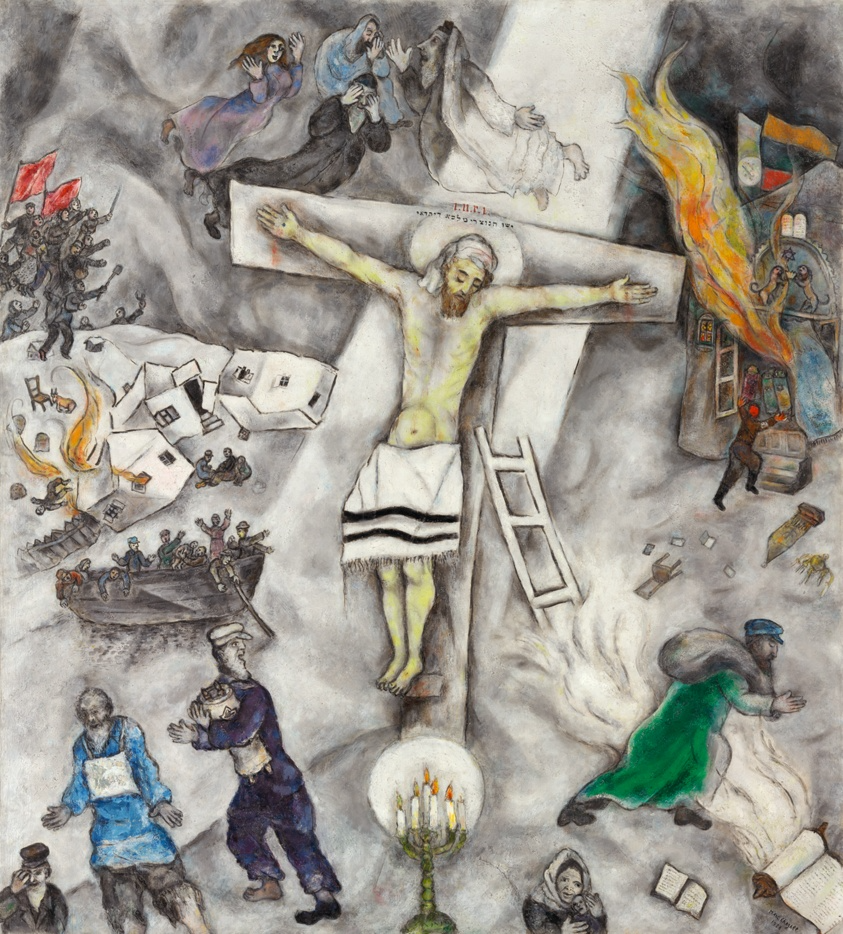

Given that our body dies, as it will, what is it that we—this self—actually are? Just because the possible answers are mysterious does not mean that they are not there. All this is unfathomable in the same sense that the most foundational episode of Western culture—the crucifixion of Jesus—is also unfathomable. God so loved the world that he gave his only son to die for us. The whole idea seems so ridiculous, so weird and just bizarre, so foreign to our super self-confident, so increasingly nervous, secular world. And yet observation tells us this idea inspired one of the world’s greatest religions; it was, and in a way still is, at the heart of our culture in ways that we don't realise. Supposed atheists, for instance, like the communist and socialist leaders subject to the brutality of Nazi prisons, wrote about their fate, their destiny—something that seemed outside of themselves—which gave their struggle and their suffering meaning, a redemption rooted in suffering that gave them strength.

What is presented to us, then, is a subversive underworld within our consciousness, beyond the facade of the materialist frame. In the dark moments of self-reflection, we know there is something else, another storyline that refuses to go away, that is always there, that our empirical eye can see evidence for all around us. That suffering is more than just suffering—it is not just one thing; it can then lead into new worlds that we are afraid to explore but are drawn to just the same, to a sense that goes beyond the ever-more tiring world of stuff and status.

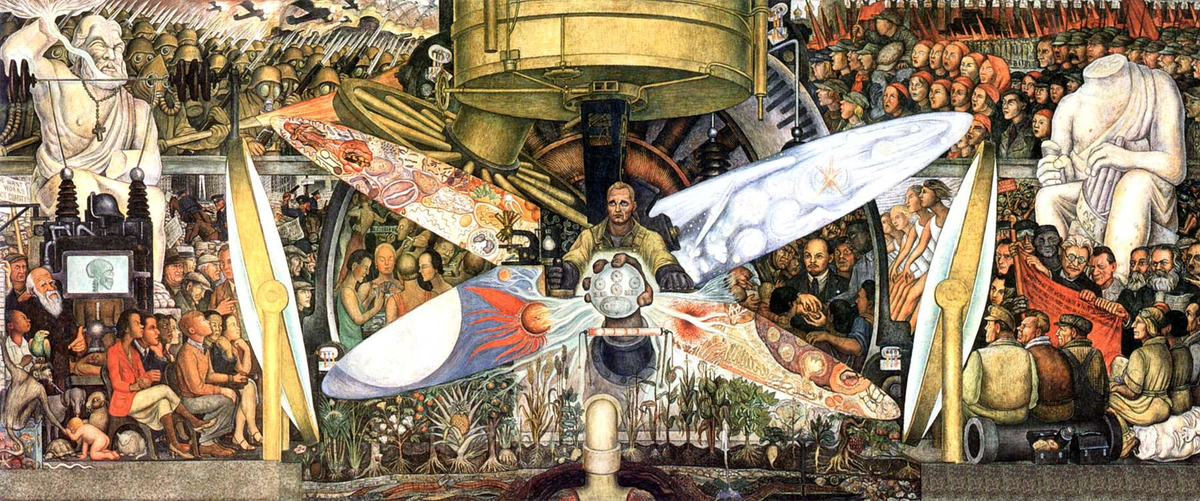

We are focused so far, then, on the person, the personal experience, but before finishing, it would be worth acknowledging that these dynamics work on a social level as well. Sociologists have come up with the concept of social fate, a willingness to serve the social, the collective interest. In the aftermath of the hardships and horrors of World War II, the extreme suffering of that experience made people realise there is indeed a society, and that we need it to look after us; that it is in the social that we derive meaning and security, rather than in our individual existence. The idea, then, is that this all started to end in the 1970s, and by the 1980s, we had entered—or maybe re-entered—the obsession with the self, our individual desires, our consumption, our status. The wheel turns.

Another, more specific example is the exceptional success of the Mondragon cooperatives in Spain, which grew to be the largest complex of worker-owned organisations in the world. The project was initiated in the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War; it was against this background of mass killings that gave workers the collective will to work together for their common good. Suffering, it seems, focuses the mind on connecting with the other—or at least it can. When I was young, I read the quote from Hegel that said that war was "ethical health." I was revolted by the idea, and I still am, but I've come to see that there is an element in what he is saying that is true.

So all of this is very confusing. I have opened up a number of boxes here and not elaborated on them that much. We will come back to a lot of them. The plan at the moment is to lay out the field, to view the landscape. This is the whole point—as you have probably come to realise, this podcast, at least at this stage, isn’t supposed to be a nice affirmation of what we already know. It's about opening up some of those doors we never wanted to open but are sort of driven to, not least because the stories we are being told—all that calm, reasonable, rational stuff—are simply not working. In fact, as we are increasingly aware, it is taking us to hell. It's an enormous pride-before-a-fall thing, and the whole point—as you’re probably tired of me saying—is not to solve these ambiguities, but to sit with them for a while. And we are piling them up.

You might think what we are dealing with here is psychology, but if so, it is a psychology that leads unavoidably on to something else—this world of the spirit, as we are calling it. We’re not quite sure what it is all about, but we are planning to go over the walls of some citadel with all the stuff, whatever this stuff means.

Let's just summarise. We have the ambiguity that suffering disrupts our notion of the rational, calm world; that this leads to a confusion, that suffering seems to be both bad but also good, in so much as it can lead to personal transcendence on the individual level and social fate on the collective level. And there is then a confusion on what this means for how we choose to act. It seems we are presented with nihilism—a purposelessness or emptiness—but at least if we trust some of the greatest wisdom traditions, it is this very vulnerability that opens us up to another world. Not just the personal resilience, but the collective strength to take down the empire we are up against—the empire that is taking us to hell—that gives us the power to create the new world. Could all be heady stuff, could all be rubbish—who knows? Let’s continue to see what happens.

As always, you can sign up for nonviolent civil resistance with Just Stop Oil in the UK or via the A22 Network internationally.