🛐 Glory Be to God: On Prison, Protest, and Adversity

Civil resistance won’t succeed on material facts alone — faith, suffering, and humility might hold the key to revolution.

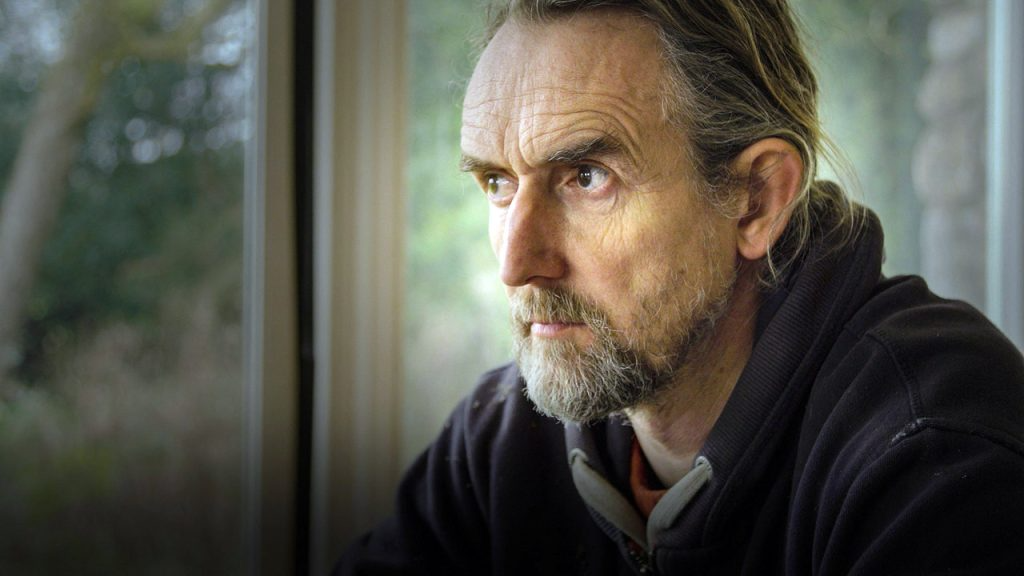

The following is an edited transcript of my first talk after release from prison. It takes place at the Kairos centre, London and you can also watch the original recording. (Sorry if I’m a bit of a sub-optimal speaker; you can blame the Prison Service for reducing my social skills!)

From time to time it is good for us to encounter troubles and adversities, for troubles compel us to search our hearts.

- The Imitation of Christ, Chapter 12, “On the Uses of Adversity”

For eight years, I’ve tried to persuade the great British public to engage in civil disobedience. The results have been mixed. Many have stepped forward, but not enough have gone to prison to force real policy change. If it takes 500 people in jail to tip the balance — maybe 1,000 — why do we stall at 200 or 300? There is always a social tipping point at which governments will change course. The only question is whether we cross it.

In this piece, I want to explore how this has been affected by three key arguments around materialism, postmodernism, and religion because it seems evident to me now that materialism alone hasn’t done the job.

I. Materialism: It Is What It Is

Here’s the familiar case. We’re at 1.5°C of heating and, on current trends of roughly 0.4°C per decade, we will hit 2°C within about ten years. At 2°C, we trigger major tipping points in the Earth's system. This is not abstract theory; it’s the physical world: rising seas, melting ice, supercharged fires, methane releases, crop failures. Emissions are not falling fast enough to stop it.

Two degrees of warming implies roughly a billion people on the move in the global South — twenty times the number of refugees at the end of the Second World War. In prison, I reviewed the 2024 literature and did the PhD student exercise of adding up the feedback compounds across decades. By the 2060s, a 5°C increase is not unthinkable if we continue to falter.

A major industry report this year suggested four billion people would die at 3°C — half the human family. The British insurance sector put that in Appendix A. The Guardian's headline mentioned a 50% GDP hit. You had to reach paragraph four to find the body count. Pensions first, corpses later.

Add the Atlantic overturning risk (AMOC): there is a decent chance it will collapse by mid-century, bringing deep cold across the North Atlantic. Imagine ice on the Thames and −10 to −30°C winters. Suddenly, it isn’t just “those people over there”. It’s us.

Materialists also warn about compounding and infrastructure tipping. Construction plans for Miami’s seawall assume that labour prices, supply chains, legislation, and public finances will stay the same in the coming decades. It's rubbish. Under compound shocks and fiscal stress, it’s far more likely that they will half-build it and then evacuate Florida.

This argument is everywhere, and it’s true enough — yet it hasn’t delivered the numbers willing to risk prison. Which suggests we need more than “it is what it is”.

II. Postmodernism: You Cannot Tell

Traditional activism balances two scales: the cost of the climate crisis and the cost of incarceration. The move is to say, “Both are bad, but the crisis is worse, so off you go.” That assumes the “cost of prison” is objective. It isn’t. It is an experience — and experiences are subjective.

Postmodernism, at its best, was a liberation from having a patriarchal voice dictate what your experience meant. Women, queer people, and indigenous people asserted their own realities. We got political postmodernism. What we didn’t get is metaphysical postmodernism. On metaphysics, modernism still rules: only the material is real; religion is either delusion or a private hobby you keep to yourself.

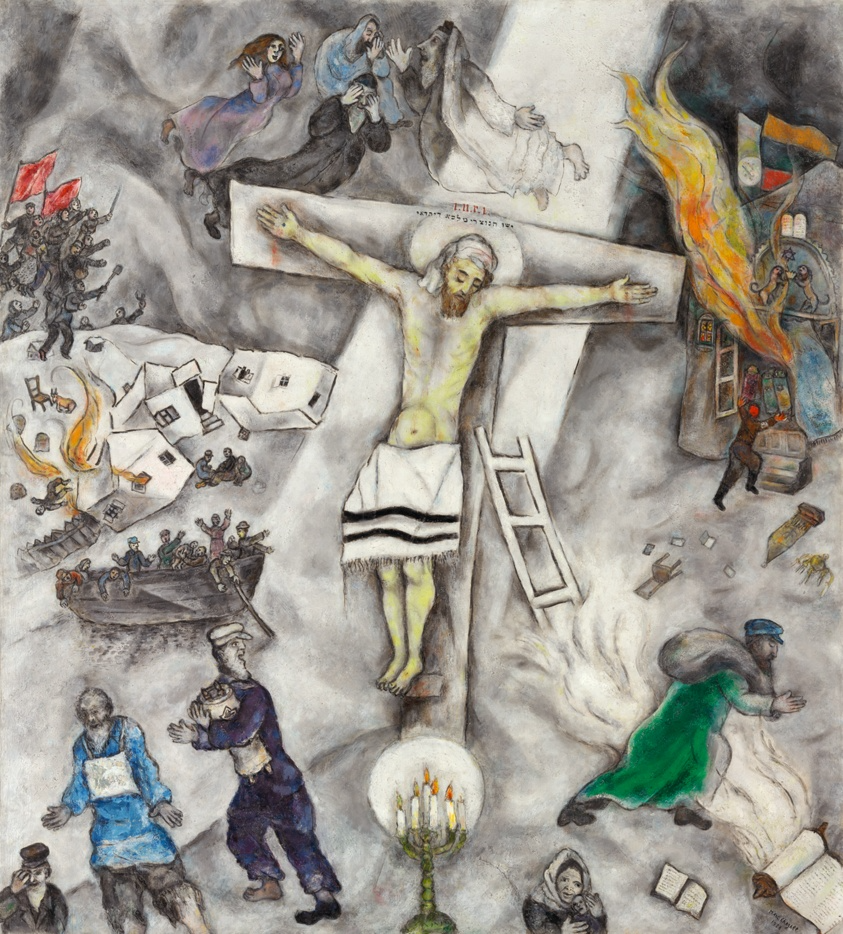

Here is my unfashionable truth: some of us love going to prison. Not everyone, obviously — pluralism is the point. But the love that dare not speak its name also exists here. Say it out loud and parts of the secular left come down on you: "prison is objectively bad, end of story". Yet, suppose you leave the metropolitan bubble and examine the global majority of human cultures. There you constantly encounter people who interpret suffering as meaningful, even desirable, because it brings them closer to God or their cosmology.

The Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya expected torture and met it calmly. Burmese tribes prepared for war with painted faces and ritual composure. In civil rights footage from Birmingham, 1963, there’s an eight-year-old girl running towards the police coach to be arrested with her mates. People are not machines. Meaning changes the power of pain.

Let me illustrate from my own experience. After long court days, the highlight in prison is Friday canteen — polos, dried apricots, tiny luxuries that make you twelve again. I returned one Monday to find a temporary cellmate had nicked the lot. I was livid, but the corridor screw shrugged it off. Yet suddenly I laughed because the penny dropped: all you ever have is your being. They can take your tat but not your soul. You can read that in spiritual books, but prison makes it visceral.

There is a growing body of literature on post-traumatic growth. For example, 10–20% of Vietnam veterans suffered PTSD, yet around 75% reported positive growth a decade later. The worse the ordeal, the greater the growth. We know this in miniature: the Couch-to-5K running program is horrible until it isn’t; the joy comes precisely because it was hard to achieve. Yet when it comes to jail, we cling to the dogma that it must be awful for everyone, all the time. It’s not true. For some, hardship is clarifying and, yes even ecstatic.

III. Religion: Glory Be to God

Now for the bit that makes atheists grumble. To be clear, I’m not talking about “spirituality” as a private lifestyle but about religion as a collective, institutional and material force — something that shapes public action.

The concept of religion as a separate sphere of life is relatively recent. In pre-modern Europe, faith saturated law, daily life, politics. The British told India it had “Hinduism”; people previously just lived within a sacred cosmos. Secular modernity carved religion off, privatised it, and declared the public sphere neutral. That settlement is not an eternal truth but a historical phase. And it’s not working.

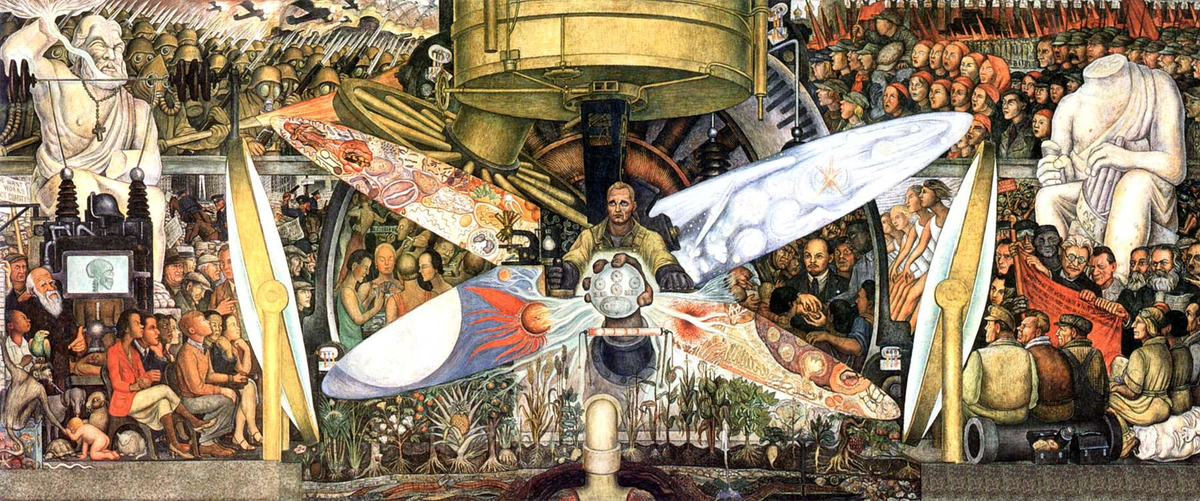

Consider classical civil resistance periods. The US civil rights movement ran through the Black Church — Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC. In Brazil, workers' movements flourished with liberation theology. Leipzig prayers led people into the East German streets before the wall fell. The Catholic Church supported Solidarity in Poland against the Soviets. Gandhi in India. The Philippines in ’86. Burma’s monks. Social science redescribes all this as “mobilisation capacity”, because it cannot admit the obvious: people risk death because they believe God is real and love is stronger.

Take these two images. A priest faces down a gang with guns and says, “You can shoot me. Jesus will still love you.” Often, they do not shoot. They cry. Why? Because they’ve just witnessed the most beautiful thing: a human being possessed by something beyond fear. Now think bigger. Picture 300 landless Brazilian peasants walking slowly towards hired gunmen occupying land. The peasants encircle them in a human chain and the mercenaries put their guns down. Again, a stunning display of human spirit. If you reduce this to tactics, you miss the point. It is grace made visible.

You don’t have to share the metaphysics to see the sociology. Eighty percent of humanity is religious. If you insist that only dead matter is real, you are simply outnumbered. I’m not asking anyone to believe what I believe; I’m asking for movements to speak my language — the language that actually moves people.

Here is the strategic nub. It’s irrelevant how prison “is” in some objective sense. What matters is the decision to interpret it as an offering, a training ground, a way to burn off the ego. I did not have a great time despite suffering; I had a great time because it was hard. The theft of a bag of apricots became a small annihilation of self — five minutes of grace — and that was enough.

Most people do not make life decisions by spreadsheet. They make them by faith, in community. So we need weekends, gatherings, liturgies of courage, where people experience the thing they cannot reason their way into — and then, quite calmly, they go to prison.

I want to conclude with the words of the theologian Karl Barth. After the First World War’s industrial slaughter of 30 million young men, he said modernity was a sick joke. The rationalist liberal order declared itself sensible and humane — and marched a generation into the meat grinder. Today, with billions of lives on the line within decades, secular modernity is once again performing like a bad joke. If the purely materialist story could have saved us, it would have done so by now.

Religions have made revolutions because they free people from the fear of death. If you won’t go as far as God, at least grant yourself a better story than “we’re clever and doomed”. Come and experience a new way of being.

References

- The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis. (c.1418). Chapter 12: “On the Uses of Adversity.”

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2023). AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Geneva: IPCC.

- Lenton, T.M. et al. (2019). “Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against.” Nature, 575, 592–595.

- World Bank. (2018). Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Munich Re. (2024). Climate Change and Systemic Risk: Global Insurance Outlook. Appendix A.

- The Guardian. (2024). “Global GDP faces 50% collapse from climate risk, say insurers.” (Headline coverage of the Munich Re report).

- Rahmstorf, S. et al. (2015). “Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation.” Nature Climate Change, 5, 475–480.

- Post-traumatic growth: Tedeschi, R.G. & Calhoun, L.G. (2004). “Posttraumatic Growth: Conceptual Foundations and Empirical Evidence.” Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18.

- Children’s March, Birmingham, Alabama. (1963). Civil Rights Movement Archive. https://www.crmvet.org

- Havel, V. (1985). The Power of the Powerless. Eastern European dissident writings, influential in 1989 uprisings.

- Liberation Theology: Boff, L. & Boff, C. (1987). Introducing Liberation Theology. Maryknoll: Orbis Books.

- Barth, K. (1932–1967). Church Dogmatics. (esp. Barth’s writings after World War I).

As always, you can sign up for nonviolent civil resistance with Just Stop Oil in the UK or via the A22 Network internationally.