😡 It's Time To Get Emotional

What if emotion isn’t the enemy of reason, but the very force that makes revolution possible?

Now that I am free, we can continue The Spirit Of Revolution podcast, starting with the release of the previously censored prison recordings. In this episode, I explore the tangled relationship between reason and emotion — and how this tension shapes not just our inner lives but the course of history itself. We’ve long been told that reason should lead and emotion should follow, but what if that story is upside down? What if the truth is that we can’t make a single decision without feeling — that emotion is not the opposite of reason, but its foundation?

From the glass box of a courtroom to the shouting voices of prison, from a childhood of repressed emotion to the fiery eruption of ACT UP in the face of AIDS, I reflect on what it means to reclaim feeling as central to both personal transformation and social change.

This podcast dives into the power of emotion — not as weakness, not as irrationality, but as the raw energy of human connection, decision-making, and resistance. Join me as I explore how the emotional turn opens the door to a new kind of politics, a new kind of revolution, and perhaps even a new civilisation.

Listen on Spotify, Apple, Soundcloud or wherever you get your podcasts. We've worked to improve the prison phone sound quality and each episode will come with a transcript below and video version on Youtube for reading along.

Episode 5 - Emotions

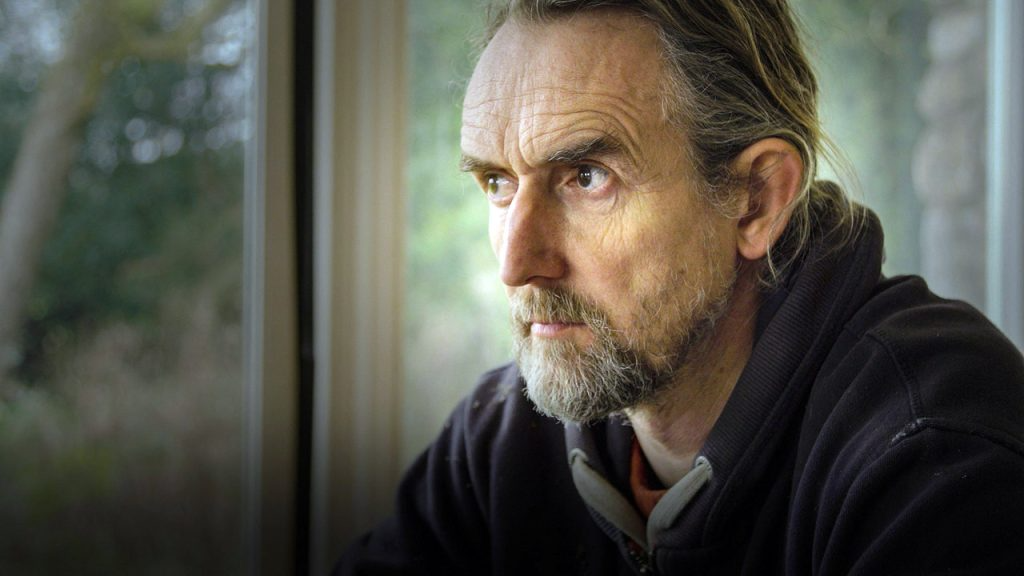

I'm writing this on the Sunday afternoon in Wandsworth Prison, London. In the background, there's a man yelling and swearing out of his cell window. It happens often, several times a day. Three days ago, I was given a five-year prison sentence; my co-defendants got four years. When we arrived in the courtroom, it was a new, bigger space. We were put in a large glass box in the centre of the room. It was surrounded by seating areas for the public, the press, the lawyers, and, at the end of the room, sat the judge. I was not expecting such a big spectacle. The room felt full of expectation and drama. I already had an idea of the sentence I would receive—the judge's already said that we were looking to go to prison for quite a long time.

The judge read out the sentence, she stood up, and left the court. I think I thought, "Okay, that is it." I got up to leave the glass box and return to the prison cell. Then I looked back behind me, and all our supporters were crowding against the glass, and the co-defendants were touching glass from the inside. It was all very emotional. I felt a bit silly for the moment. I saw Chris Packham, the TV presenter. He looked shell-shocked. I smiled at him and gave him the thumbs-up.

I was brought up in a severely Calvinistic family. I didn't realise this until I left home. I can't remember my parents telling me they loved me after the age of about 10, and from that point onwards, there were no hugs. My parents were brought up during the Second World War. It was a hard and repressed childhood, and I think they carried the weight of it with them all their lives. In my 20s, I consciously decided to reprogram myself, as you might say, or at least I learned to be a new self. Hugging was back in, but I still have that voice inside me going, "No emotion, please."

During dramatic moments in my life, I tend to feel detached, hence my embarrassment at the sentencing. There is this new idea—a new culture, you might say—that has grown up in recent decades, that displays of emotion are okay. Emotion is part of being human. There is not just reason; we can be emotional. But actually, that's not quite right. There's something more fundamental that has occurred, especially in the social sciences. It's not the old dichotomy between reason versus emotion or what is presumed to be irrationality. It's the realization that reason cannot exist without emotion in the real world, rather than the rationalist, reductive world of those 18th-century gentlemen. Then again, that rules out any role for emotion. It has actually turned out that they are, in fact, both part of the same thing. According to empirical observation, you cannot decide matters without emotion. Reason, in practice, cannot exist without it.

This has been shown in a stark way by research where a person that has brain damage and could not feel their emotions also was totally unable to make decisions. Of course, in a way, this is obvious. The ideological fantasy that we are cold, calculating machines is nonsense. In the real world, we feel, and we decide at the same time. When people say they have no feelings involved in making a decision, they're just in denial.

Certainly, if you challenge them on this, then they certainly get emotional about it. Their emotion is ideological; it's not based upon observation. So we have a game: this ongoing feat—the supposed tool of the rationalist, empirical observation—undermines the idea of pure reason. In reality, things are messy. The reality is we've got our categories wrong. We feel a decision; we find ourselves having a reason. This is not irrationality; it's what we might call the non-rational. The rational is just some ideal-type thing stuck in the head of all those gentlemen. As such, this realization is another nail in the coffin of the idea that there's some atomized decision-making self.

So, you might justifiably ask: where does the emergence of a feeling come from if there is only one self? We are back to the uncomfortable idea of there being no foundation, no ground. We are back to being as suspended; we only have the present moment—this moment of agency within a sea of received thoughts and emotions. But we are not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. There is obviously such a thing as sitting down and consciously focusing on something, but it is clear that this is the exception, not the rule. And even when we do this, we find ourselves integrating a whole bunch of feelings and intuition. It's complicated.

The more we look at it, the more we find that our language here is problematic. In a way, what is going on is beyond language. But the good news is that life goes on. In fact, over the last few decades, there's been a transformation in how we see emotion, in particular, in how it relates to personal and social change.

The process of acknowledging and encouraging emotion has been at the centre of new therapeutic approaches—something my parents' generation was never able to benefit from. There's been a similar development in the public realm. As it happens, my top hero of the 20th century, the most effective social change person in my view, was not Gandhi or Martin Luther King—it was Larry Kramer of Act Up, the gay campaign group.

Of course, Gandhi and King were amazing people, but they were set within a rather repressed, solemn, reasoning culture—the culture of my parents' generation, with its dysfunctional response to the wars and traumas of the 20th century. When the AIDS epidemic spread through the gay communities of New York in the 1980s, this was the culture that dominated the public sphere. It was the received norm: monotone speeches, euphemistic language, denial, and nothing was happening. The bodies of gay men piled up in hospital corridors, neglected and left to die.

Then Larry came along, and all hell broke loose. "Get out on the streets, otherwise you're gonna fucking die!" Six months of explosive emotion, and everything changed. People started to be treated with some dignity, and new drugs were introduced. Of course, a lot more was going on, but it seemed like something in the general culture was starting to shift. When I researched social movement theory at King's College, I found out what was called the social turn. Social change did not happen just because of structural openings in the political context. Change happened because people got emotional, and they showed it. And arguably, distrust of other factors—it's all about the drama, isn't it?

The point here is that people change when people get angry with them. We all know this from our personal lives. Not always, of course, but at least when you're dealing with entrenched power, calmly reasoning with people is paradoxically unreasonable—irrational, even. It doesn't work. According to social scientific occupation, there are nuances here. It can't be rigidly hateful, and it cannot go on endlessly, but it's definitely part of the mix. This is what Larry Kramer was showing. It's not a matter of policy options; it's a matter of feelings.

When he said, " I hate you," to an interviewer, he was just being honest—an authentic, real person. We all have feelings of hate. He was describing how he felt as an imperfect human being. This, then, is a big step forward from the paradigm of Gandhi and King, where everything was set within a frame of moral reasoning. And of course, this is a simplification.

Obviously, King showed plenty of emotion, but there's something about the sensuality of emotion—rather than just reason—which leads to effective persuasion. Maybe, in fact, it would be good to drop this notion of reason altogether. Thinking back to the trial, there was one point where the judge left the room—not that emotionally mature, you might say—and I blurted out to the two prosecution lawyers, "Why don't you do something? It's been totally incoherent!" It was the only time that I saw them getting ruffled—when I made an emotional outburst.

At the end of the trial, a good friend of mine, a Black woman who'd come to the UK from Ghana, shouted at a prosecutor about their complicity. I expect that these two incidents had more impact on them than all the dry legal arguments. Sometimes, someone has to let it all out. The emotional turn, then, can be seen as a major change in how we see the process of social engagement. It is rooted in a more general feminist confrontation with the repressive male metaphysics of the last 300 years—or maybe much longer—meaning the imposed common sense of the rational has been challenged by the emergence of the feeling.

It is feeling that underlies the sociability which is essential for healthy human communication. We encourage them to move on from this imposed notion of the solid, rigid, atomized self. The "me" is not a thing, but an ever-changing ecology.

An intermixing of internal and external flows and waves of consciousness and the unconscious. This reflects the findings of modern time. It's clear that a new paradigm of understanding ourselves is being offered to us. It is also very different to some idealized, perfected notion of enlightenment—a process whereby Eastern traditions are squeezed through the frame of Western individualism.

You may have thought that the previous episodes on the Self, the world, and the time were directing us to some form of individualized detachment—the stereotype of what gets called personal growth—but this, in fact, is just another form of 18th-century ego-based atomization. "Ocean of I on my own, are on a journey on the rest of the world, has nothing to do with me" is actually an outcome of privileged sadism, just another type of othering the Other.

Now, where we're moving towards is the intrinsic emotionality of everyday social life: being in the thick of it, without separation, but without rigid detachment either. Paradoxically, it's not attachment to your own detachment. What this broader feminist metaphysics has brought back into the frame is the spirit of pagan, gritty embeddedness.

We can say then that we are in this world, but we're also transcendent from it at the same time. We are accepting our suspendedness on this journey of engagement. Entering into this spirit of revolution, we discover that emotion is essential to communication, essential to making decisions, and critical to social confrontation. It is at the heart of our humanity. It is not irrational; rather, it is non-rational.

We will look at two other aspects of the non-rational, as we’ll call it, before going over the walls of the citadel—that being the ruinous division between the secular and the religious. And then I hope we will see a whole new landscape open up. That, then, is the direction of travel.

As we build upon the pluralistic sense of metaphysics, we can, I hope, see that the new status given to emotion gives us the potentiality for a deep cultural transformation—something which is going to have to be a major plank of a new civilization that emerges from the devastation of the Old World, this world we are still trapped within. The therapeutic and the psychological will take over from the economic and the political, the miserable sciences of greed and stuff. And yet, to remind ourselves again, we are not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Economics still has relevance. We are looking at a radical rebalancing, not an elimination. The notion of totality, the idea of total victory, is part of the old way of looking at things—the way of us or them.

We are looking at dissolving the rigidity of opposition into the connectivity of ecology. This is a developing theme of this podcast—this pluralism. Next time, we'll look at other elements of the nonrational.

As always, you can sign up for nonviolent civil resistance with Just Stop Oil in the UK or via the A22 Network internationally. If you want to get involved in the democratic revolution, join an upcoming Welcome to Assemble talk.