⚖️My Trial Was A Sham

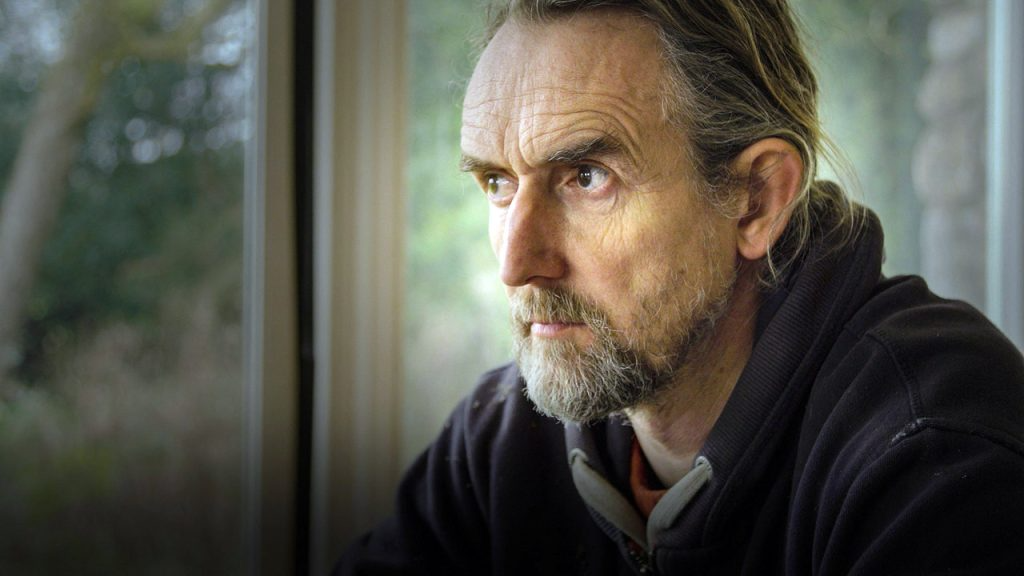

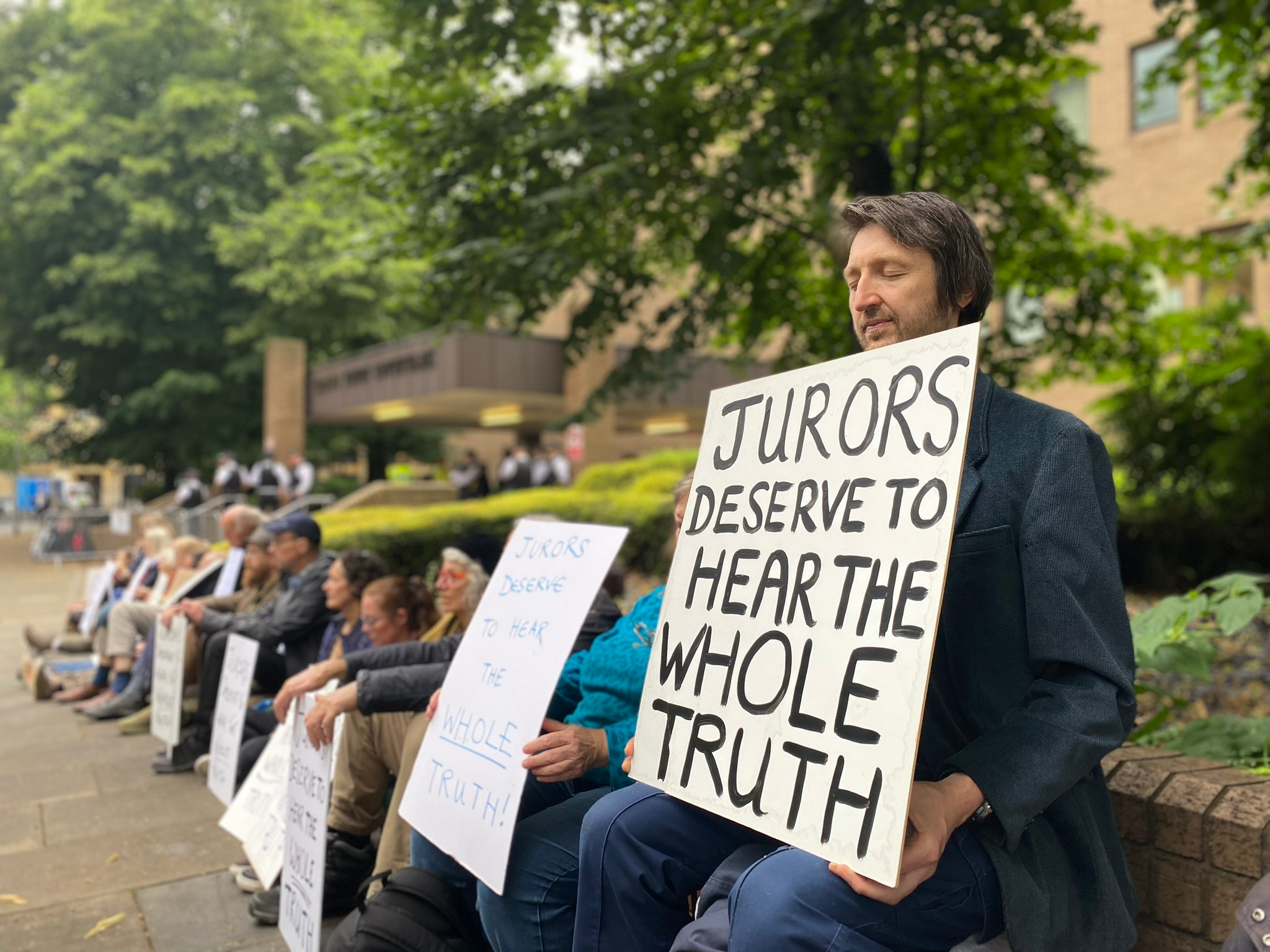

This is my closing speech to jurors in the Whole Truth Five trial. Afterwards I was found guilty and given a 5-year prison sentence.

Note: This speech was transcribed from a prison phoneline. You can listen to the audio version on Spotify/Apple Podcasts or watch the Youtube video with subtitles.

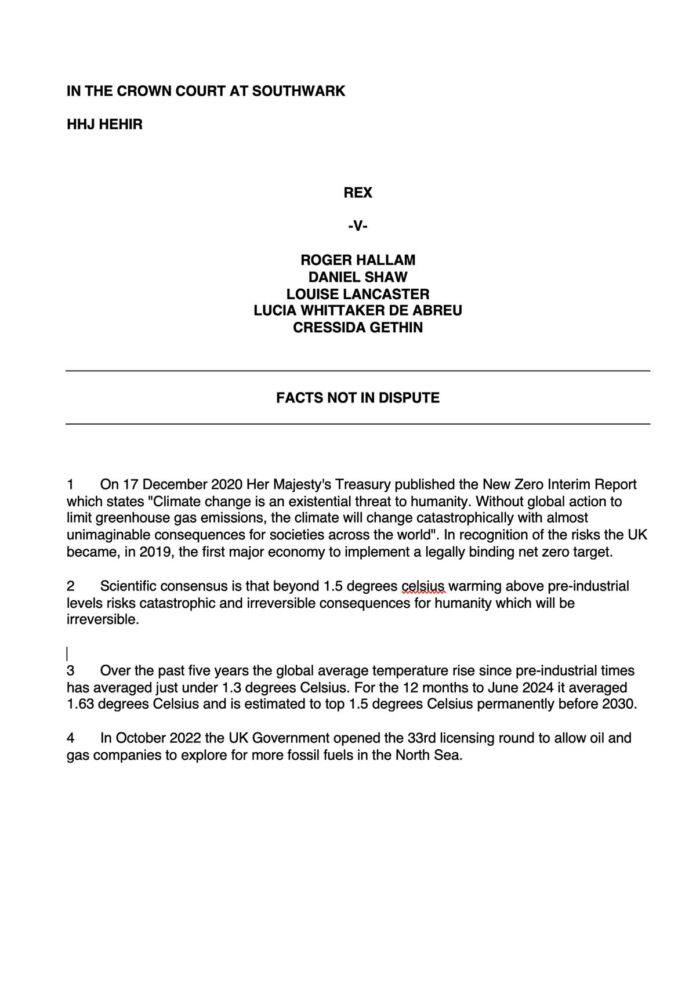

I would like to start by acknowledging that this has been a strange and difficult trial. As the judge has said, he has never had defendants dragged from the court and put in prison, and it's not usual for the jury to be sent out so often, prevented from hearing what a defendant has to say. I want to apologise for the commotion; it is not how I would like a court case to proceed, but I'd like to draw your attention to a very important outcome of this disruption, namely that the judge was persuaded to change his mind and allow you to see four relevant, agreed facts about this case—about the harm and the criminality that myself and my fellow defendants were intending to draw attention to and prevent.

These four simple facts shine a light on a world of evidence you were prevented from considering in this trial, and it is common sense that if you are not allowed to see both sides of the argument, you cannot be sure of guilt. It is also, therefore, obvious that this has not been a fair trial—not by any common-sense definition. Is this how justice should work? You have heard already, you have to be sure to convict. In any UK court, you have to be sure. As a lawyer said in another trial I was involved in, even if you are just a tiny, tiny bit unsure, the law says you have to find the defendant not guilty. This is because a defendant is innocent unless proven guilty. The prosecution has to prove beyond doubt that there was no reasonable excuse in this particular case, as laid down by an act of Parliament.

Of course, the judge has instructed you that the facts about the massive harm created by the emission of greenhouse gases are not relevant in this case. But you should note that he has also conceded that, to quote, “The facts are as you find them.” You have to interpret those facts, you have to make sense of them, you have to decide what it means—what a fact, an agreed fact, means when it says we face a catastrophe, catastrophic consequences as a country if emissions are not stopped. We face some cold, hard facts in this trial. The judge might want to avoid them, but you make up your own mind. The facts as you find them—this is your job. This is what the law on jury equity means. You have to make up your own mind. You're independent in this court. It is a great responsibility, and given the agreed facts, your responsibility goes well beyond this courtroom.

This charge, as you know, has two aspects: the charge of conspiracy—conspiracy to cause a public nuisance—and then also the charge of public nuisance itself, public nuisance without a reasonable excuse. I will deal first with the conspiracy element. I was not part of any conspiracy. I have said so on oath. I was not party to any agreement to go to the countries. I did not go to any organising meetings. I received no paperwork or documentation. I took no trips, and I did none of the organising. It is not up to me to prove to you these things, but for the prosecution to prove that I did receive paperwork, go to meetings, etcetera. And you all have noticed that they have provided no evidence—no evidence at all. And the reason is because there is no evidence. I was simply not involved.

The prosecution says they have powerful evidence. Notice they didn't say conclusive or overwhelming evidence. What they mean to say is there's some evidence. Some evidence is not proof. You cannot be sure, and if you cannot be sure, then you cannot convict, because you don't have the documents, the equipment, the reports of meetings—there was none.

And so, in my case, they have to try and prove my guilt with the single 20-minute Zoom talk that I did. That's it. As I've said, I've done hundreds of these sorts of talks on civil disobedience, making arguments for people to be involved in specific civil disobedience campaigns. Never before have I been arrested for such a talk.

When I was arrested, I expected to be let out the following day—not put in prison on remand for four months and then put on a curfew tag for one and a half years so I couldn't go out late in the evening. Most of the speech is about the general reasons and arguments for why action is needed, why, and how civil disobedience works. As Dan Shaw introduced me, I was there to give the reasons to step up. I was there to give reasons; I was not part of a conspiracy.

It seems the whole case against me revolves around just 10 lines of the speech—that I knew that the project needed around 60 people, that I said, "We need to get involved." So, on the point of the 60 people, the fact of the matter is, this was widely known. Lots of people knew we needed around 60 people. That does not mean that I was involved in a conspiracy, part of an agreement to take joint action. Knowing information might be part of a conspiracy, but it's common sense that it does not provide conclusive proof. For that, you need corroborative material evidence. As I said, evidence of going to organisation meetings, activities, possession of paperwork, etc. Just knowing something in itself is clearly insufficient.

And when I said, "We," I was saying we are the movement in a general sense. Again, in and of itself, it proves nothing. In contrast, if I'd said, "We need to step up, and I want all of you to join me in a planning meeting next week when I'll go through all the details," then that would have been clear evidence. I did not say that, did I? Because I was not involved. I was not there to make an agreement; I was there to make an argument, to give reasons. That's why the person after me was going to, to quote, "Go into exactly how it works." Why was this? Because I did not know those details. I didn't know about the future meet-up. I knew nothing about what was happening, when, and where. I was there simply to do one thing—to make a speech.

To conclude on this, to be sure, you need to have evidence of concrete actions, material evidence, to be totally sure of innocence. You have to know. You need people to know nothing about the conspiracy. In the middle, as it were, I myself knew something, but that was it. You can speculate that I knew more and I was involved in more things, but self-evidently, you cannot be sure. And because you cannot be sure, you cannot convict.

And there's one more thing to be said about the prosecution case against me. What are the implications for protest? If there is a campaign, say, against pollution in your locality, and you have suffered the effects of that pollution, and your children have been in hospital, it's likely you'll be asked to speak at a meeting in support of a demonstration against that pollution. I'm supposing that in that general demonstration, people are arrested. Some people engage in civil disobedience, and then the police knock on your door and charge you with conspiracy. How exactly are you going to defend yourself if you simply made a speech? You cannot prove that you weren't further involved. But if you convict me on this basis, then, well, this could happen to you. You see what I'm saying?

As soon as you depart from needing material evidence—documents, organisational details—then you enter dangerous territory, don't you? You can be convicted for words, for making a speech, for thoughts. There's a name for this: a police state. Is that what we want? Could you find yourself standing in a dock like me?

Let's be clear. I have organised civil disobedience actions in the past, but I did not organise this one. I'm under oath, and I'm telling you the truth. If I was involved, I would tell you. But on this occasion, I was not, and I hope that's clear.

And then there is the matter of public nuisance. This could not be more different. It happens that no one is denying the evidence—the evidence is overwhelming. There's no question about it. There was a public nuisance. This is not the charge. The charge, the law is clear—we are charged with public nuisance without reasonable excuse. That is the law that was passed by Parliament in 2022, and you have to look at the law and the whole of the law. That's your job.

And obviously, this has to be the law. It would be totally unjust to have a law that did not allow for people to cause a public nuisance in particular circumstances. An obvious example of this is the classic scenario of shouting "fire" in a theatre. Self-evidently, you're causing a nuisance. You're stopping people from watching the play—no question about that. At the same time, you're doing the public service. You're getting attention to the fact there is a fire, and people in the theatre could die if they don't find out and act accordingly. We see this situation all the time in history, in the movies. It's a well-known situation. It's common sense, obviously—there has to be the possibility of a reasonable excuse.

So that is step one—establishing the possibility. The next step is also obvious—it all depends on the evidence, doesn't it? On the agreed facts, the cold, hard, physical facts of the consequences of taking action or not taking action. So in the theatre example, you might consider how big the fire was, how many people there were in the theatre, how quick it was for them to get through the exits.

So let's look at this case. Let's suppose that a group of people went onto the motorway. They stopped the traffic; no reason was given. It was clearly a public nuisance—no question about that. There were long delays; people were stopped from going about their daily business. There was no excuse. It's a clear-cut court case, isn't it? We can all agree on that. The jury is going to find the defendants guilty—job done.

Except, consider the following situation: the prosecution and the judge have conspired here—we can use that word—to prevent critical evidence from being shown to the jury. It turns out, in fact—note those words, *in fact*—further up the motorway, there was going to be a terrorist attack, and vehicles could have been blown up. In other words, if people had not gone onto the motorway, people would have died. People were causing a public nuisance, but the new facts change the situation, don't they? Totally. It's common sense that the road was blocked by people who were heroes. They would have had an overwhelming reasonable excuse; they were saving lives. No case to answer. Not guilty.

So what happens if what I've just described has happened in this trial? What if the prosecution was, in fact, hiding evidence from you? There's a question for you. The question is, of course, how do you know? Maybe in those 200 pages of defence evidence, you'll find important considerations. Can you be certain? No, because you simply don't know. So can you be certain that we had no reasonable excuse if you haven't seen the evidence? If the evidence exists, what's the big deal? Why doesn't the judge just let you look at the defence evidence and hear the expert witnesses? And you might ask, well, what's the big deal? I mean, the prosecution had a full week to present their evidence—all well and good—so why not let the defence produce, what, two or three hours of evidence each? I'm sure it's crossed your mind—have they got something to hide here? Why do they keep sending us out? Don't you trust us or something to make up our own minds?

Actually, there is a third possibility here. The first possibility was that there was no threat to life. The second possibility was that there was a threat to some lives because there was going to be a bomb further up the motorway. But there could be something so, so much worse—concrete, overwhelming, physical, scientific evidence of a threat to the lives of hundreds of millions of people. The lives of the people in this courtroom, our children's lives, the lives of those whom we love. How do you know that this isn't true? Again, you simply do not know. You do not know because you have not been given the defence's evidence. You have not been allowed to hear the defence's expert witnesses—the professors, the world-famous scientists. You cannot be trusted, for some reason, to hear the whole story, the whole truth.

And this is the point, members of the jury: to convict, to find defendants guilty, you have to hear all the evidence—all the evidence—not 20 minutes with constant interruptions by the judge telling you what you can and can't say. This is not a police state, is it? So let us speak. And remember, if you can't be certain, you can't be sure. And if you can't be sure, you can't convict. Even if you're 99% sure, then it's not guilty. That's what the lawyers say.

Except this is not the whole story, is it? Something happened during this trial that didn't actually go to plan. The judge and the prosecution thought they had it all sewn up—they thought the job was done. No evidence of reasonable excuse; open-and-shut case. What they didn't reckon with is five experienced campaigners who know what a rigged trial looks like when they see one. We were given no legal defences. The judges used to give legal defences so we could have our say. But now they've overstepped the mark. They decided no more defences—20 minutes, please, and then sat down. They changed the rules of the game, and so did we.

We refused to betray our oath. We refused to betray you, members of the jury, by not giving you the evidence, by refusing to not give you the evidence you need to make a fair judgement. After all, isn't it the essence of a legal system to be able to hear both sides of the case? Isn't it the essence of justice to be able to compare the disruption caused by a citizen with the disruption they are trying to prevent? In this trial, we, the defendants, were not prepared to stand by and allow the judge to undermine the rule of law.

We refuse to leave the dock because justice demands fairness. We were prepared to be dragged from the courtroom and sent to prison to defend your right—your sacred right as a jury—to hear the evidence. Some of the evidence? Not 20 minutes of the evidence—all of it. And guess what? Disruption in this case—disruption in the cause of exposing the truth—worked.

The judge absolutely refused to have anything said in this case about what he called, "climate change." You remember him saying this many times: No talking about climate change—over and over again. And then suddenly, he changed his mind. Suddenly, once we'd stood firm—hey presto!—we found four new agreed facts about, well, climate change. Why was that? Because he didn't want those facts, did he? Obviously, he didn't want them to "open the door," to use the prosecutor's phrase, to the blindingly obvious—that we did not go onto the courts just for the sake of doing so. Obviously not. We did so because there was an undeniable, objective, physical harm being created on a scale never seen before in human history.

Agreed fact No. 1, members of the jury: catastrophic consequences of putting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.That was the transformative moment in this trial. They all had it nicely sewn up, and then suddenly, they had to face the fact that this society—our kids, our communities, our whole way of life—is facing a catastrophe that's off the scale.

So what happened next? Did the judge do the decent thing? Did he accept that, yes, maybe there is a case—a reasonable excuse for actions—if you know... well, let's be real about this, if there is a real prospect that our children are going to face death by slow starvation? Did he say, "Okay, that's the truth. We should finally allow the jury to see the 250-page bundle of defence evidence?" Did he accept that it might just throw light on the case if we had an expert witness or two from, say, University College London, who, unlike the judge, happens to have spent decades researching the actual facts? Maybe the expert would enlighten us a little.

But no, he did not allow this to happen. Instead, he did the most remarkable thing, didn't he? Do you remember, members of the jury, what the judge said—this man whom we are asked to trust to preside fairly over this case? What he said was, *Oh, they are agreed facts, but they are not relevant to this case.* How gobsmackingly, embarrassingly ludicrous! Can you have agreed facts and then ask people to ignore them? Can agreed facts be any old facts? You know, like, *Oh, the defendants like a bit of fresh air*—why wasn't that put in? It's a fact, everyone agrees on it, no problem, pop it in. Agreed facts are facts that are relevant to the case. I can't believe we, in a British courtroom, have to have an argument around such a bleedingly obvious point.

Agreed fact No. 1: We face a catastrophe. We face a catastrophe—it's relevant to the case, it's part of the evidence, you have to consider it. It's your legal obligation as a jury to consider this fact—it's called the law, the rule of law, is it not? And what does it tell us about the trustworthiness of this judge? Well, we know what we think about that, because we know what he said next. He changed the goalposts, didn't he? You know about changing the goalposts, don't you? Or at least, if you have children like me, you know how it goes: you have an argument, you catch them out, and then you know what happens next—they change the subject. Goalposts have changed—there's a word for it, isn't there? There's a word for it: juvenile.

And so what happened next? Having lost the argument on evidence of the catastrophe—what he called "climate change," the objective facts—he then said, Well, it's all political anyway, and we should take it through the democratic process. That's what we should do.This is then a case where we can talk about politics, because then the judge proceeded to tell us his, what you and I call, quote, “sincerely held beliefs” about whether we live in a functioning democratic state—a “functioning democratic state”, as quoted from the Jones judgement.

So, suddenly, we're no longer talking about the law as such; we're suddenly talking about the judge’s politics. So, let's look for a moment at the politics—assuming I don't get interrupted, assuming we have a fair, flat playing field here.

The Jones judgement says that civil disobedience is illegal if we live in a functioning democratic state. Notice this is a conditional statement: if we have a functioning democratic state, then Civil disobedience is illegal. Meaning, of course, if we don't live in a functioning democratic state, then civil disobedience could be justified—in fact, it could be legal. We could have a reasonable excuse.

So, now we are in the position, in a British courtroom, of the prosecution having to prove to you—because you have to be sure, remember, remember that word—you have to be sure that we live in a functioning democratic state. And if you're in any doubt about living in a democratic state—a functioning one—then it's possible that we have a legal excuse, and, legally speaking, you cannot be convicted.

So, this is important stuff. The judge has kindly moved the central argument, the central issue of this trial, to answer the question: What sort of state do we live in? Given the centrality of this question, I presume the judge will allow me a few moments to look at this proposition in a little more detail.

Members of the jury, notice the word functional. Judges don't just put in any old words in a haphazard way in their judgments and their laws; they take their time. *Functional* was put in for a reason—because it is possible, of course, that we could live in a *dysfunctional* democratic state, and then we would be forced to consider that civil disobedience is legal. And as I've said, we could therefore have a reasonable excuse.

So, let me suggest that we could start with two forms of evidence here—assuming we're interested in evidence, of course. First of all, I would bet with the judge that if you go out onto the streets of this great city, into the streets of London, and ask people if they think we live in a functioning democratic state, I think it's a reasonable possibility that many, if not the majority, of people will laugh at you. Yes, they would have agreed a generation ago—maybe 10 years ago, they weren't so sure—but now, no.

If you want to be a little bit more systematic in considering the evidence, then I could refer you to a whole cascade of surveys over recent years that show that our politicians and politics are more distrusted than at any point in modern times. How dare I say it? As you know, I used to be a social science researcher at King's College London, where there are plenty of academics who are fully versed on the current literature on whether or not we live in a *functional* democratic state. There are plenty of experts who could come and provide evidence to you, the jury, on this area of academic research.

But you know what? You're not allowed to hear the expert evidence on this—the central question of this court case. Why is that? Because, bless him, the judge has decided that it's not for you to decide. You don't need to busy your mind with evidence. Judge Hare has already decided we live in a functioning democratic state, and that is that. Judge Hare has the quaint idea that because we have elections, then—hey presto!—we live in a democracy. End of argument.

For Judge Herir, this is nothing to do with politics; it's an objective matter. God has deemed our state is infallible and always will be. Yes, this has shown the judge to be an anti-democrat, hasn't it? When it comes to making a decision, he dictates. And there's a word for a person that dictates—we know what that is: a dictator.

Maybe the UN officials who have been sitting in on this court case might like to give the judge some useful advice on this matter. Maybe they already have communicated to the judge in a letter, but we don't know, do we? Because we're not allowed to know.

Is there a pattern emerging here, members of the jury? I think the people who will listen to this speech after this court case will be getting with the program at this point. They would have decided that this trial is a sham—the verdict has already been decided. You, the jury, are here to rubber-stamp the proceedings, to hear from the judge, and to do what the judge tells you to do. That is your duty—not to the truth, but to the judge. And as we are seeing, the judge is not so keen on the truth.

But all is not lost. Change the goalposts if you want to, but it turns out there's still no escape. Agreed Fact No. 1 still exists: we are facing a catastrophe. Agreed Fact No. 4 still exists. Take a look at it, members of the jury—Agreed Fact No. 4. At the time of the action, our supposed functioning democratic state was promoting more oil licences. It was all "burn, baby, burn," wasn't it? Remember the Prime Minister saying he intended to, quote, "max out on oil"?

So, we are forced to consider the all-important question, which is this: can a fully functioning democratic state create a catastrophe in the full awareness of its actions? It might be useful to consider a historical example here. Not so long ago, there was the idea in this country that you too could take ships to Africa, pick up slaves, take them to America, to the Americas, have them work on plantations. The estimates vary, but it's reasonable to believe that around a quarter of those people died in transit to America, and that those who arrived died within five years of working on a plantation.

This was good business, members of the jury, wasn't it? No doubt about it—the elites of this country were laughing all the way to the bank. And there was a common attitude to our national disgrace: that we need not be concerned with Black lives. They were, well, what's the word—dispensable, disposable—just a cost on the balance sheet. Was that the action of a fully democratic state? Can we say that a fully democratic state imposed torture and death on 10 million people from Africa for reasons of economic gain? No, no, no, we cannot. Why? Because it was disgusting. It's vile. It's appalling. If anyone in this courtroom suggested otherwise, they would lose all credibility, would they not?

This is what the judge in this courtroom is saying. What he's saying is appalling. What he's saying is vile, disgusting—disgusting. This is my defence. I have a right to explain myself, and I have the right to speak about this matter.

What does the catastrophe mean, members of the jury? What does it mean for the UK government, for economic gain, to promote and provide licences for more oil and gas in 2024, in 2022, in 2020? What does it mean to emit carbon at this point in history that will push temperatures over 2 degrees centigrade? That will, according to peer-reviewed papers, produce one thousand million refugees in the poorest areas of the world—in Africa, Central America, South Asia. According to the facts, the cold, hard facts: slave ships kill Black people, plantations kill Black people, and emitting CO2 kills Black people.

Not 10 million Black people—thousands of millions of lives are destroyed through this project. Thousands of millions of people will be forced to leave their homes—not forced by slave traders, but by something much, much worse: by a project to destroy the climate of those people, to turn their land into desert, to stop the rains, to starve them every year. Not for 100 years, not for 200 years, but for thousands of years without end.

Call it vile, disgusting—not in a million years does a functioning democratic state do this to innocent people. No, it does not. It does not. You can be sure—you can be absolutely sure—of one thing: that no functioning democratic state does this.

No functioning democratic state in a million years organizes a genocide on this scale. And does it end there? How do you know? Because you haven't seen 250 pages of horrors, have you? It's been hidden from you. No, it doesn't end there, does it? Because now, I will give you the worst news you are going to hear in your life. That little word “catastrophic” in Agreed Fact No. 1 means something—something that affects you in this courtroom.

You know what it means for the people of Africa, the people of Central America, the people in the hot areas of the world. What about us here in our cool temperate highlands? You will starve to death. You will see those that you love starve to death. According to peer-reviewed research, “catastrophic” is exactly what it means for your families if you allow governments to continue to burn oil and gas fossil fuels.

This is what the latest research says. It says that it's more likely than not that the Gulf Stream current in the Atlantic—the current that keeps this country warm—will collapse in the next half to quarter century. By 2050, in 25 years' time, in fact, it could collapse at any point after 2025, next year. And this will plunge temperatures down by 10 to 30 degrees Celsius in the winter. It will be like living in northern Norway. It will affect the whole of Europe.

Ask yourself this: where are 60 million people going to go when this island is covered with ice for over half a year, when you cannot grow food? We’re going to starve or we’re going to migrate. But where? When hundreds of millions of refugees are coming north into Europe out of the Middle East and Africa. Of course, you might not starve, you might say. And then you might say, “Well, that's okay then. You might say, well, not all your family is going to have to migrate, so that's okay then—full speed ahead, burn, baby, burn, max out on oil.”

There are only peer-reviewed papers after all. I mean, look on the bright side. No, I don’t think we're thinking that, are we? We know what's happening. One simple thing is happening: a crime. The greatest crime—that's what it is. And never in our history have we had a greater reasonable excuse to stop such a monstrosity. Only a psychopath would disagree.

Assuming we want to listen to the evidence—such as assuming we want to attend to that little word “catastrophic” in Agreed Fact No. 1. 250 pages—there's lots more in there. Lots more. Aren’t you starting to feel a little bit annoyed that the judge will not allow you to see that document? Aren’t you starting to feel a little bit mad that you cannot hear about what’s going to happen to you and your family, that you cannot hear from an expert witness? You cannot hear it from the horse’s mouth what’s actually going to happen to you.

I mean, this is serious, isn’t it? Deadly serious. What is going to happen? What will this catastrophe look like? Why can't we have an expert in this court?

So, you’ve heard the agreed facts. You’ve heard what it means for the poorest people in this world. You’ve heard what it means for this country. But what about London? Maybe the judge will allow me just a few more minutes to tell you what is going to happen to the great city of London by 2050.

A quarter of the buildings in the city will be subsiding because of droughts that will dry out the clay soils. Warning: four of you will have to move. Where to, you might ask? And then if it doesn’t rain for three or four months, which is highly likely, 8 million people in this city will have no water. What will happen then, you might ask? And then with the collapse of food supplies—I mean, do you remember the beginning of COVID? I remember going into a corner shop, my local shop in Wandsworth, and they’d run out of rice. Everyone was looking edgy, do you remember that?

Imagine what it’s going to be like when it’s weeks and months. There are plenty of expert witnesses out there who could come into this trial and tell you precisely what is going to happen.

When people go hungry, what happens then? When law and order collapses—law and order that prosecutors claim to love so much—these expert witnesses can tell you. They'll tell you it gets very ugly. They'll tell you people kill each other. That's what will happen.

And then there's the small matter of sea level rise. By 2050, this country—this city—will have to be evacuated because we can't keep the water out any longer. Yes, it may happen later. It may be 2070, but it may well be before then. But one thing is totally certain: if you allow the burning of more oil and gas, you can be 100% certain that this city is going down. It is done for; it will have gone. It will be under the sea.

“Catastrophic”—what do you think this word means? What does this word mean? Did you think it meant a picnic? Something, you know, neither here nor there, to use that quote from Judge Hare? Do you think that what's going to happen to this great city of ours is of no consequence—just neither here nor there?

Physical evidence, members of the jury, focus on the facts—the cold, hard facts. Yes, of course, everything I've told you is an estimate, meaning, by the way, it could happen earlier; it could be even worse. As they say, the terrorist bomb could have gone off later; it might not have gone off; it could have been okay. No need to stop all that oil and gas then, even though 1,000, 10,000—indeed, science papers say that emitting carbon will lead to everlasting hell.

So you don't need to be totally certain. Do you have a reasonable excuse? I mean, let’s look at this another way. If you go to the airport with your children and the official says to you, “Hey, there's a 50% chance of your plane crashing with your kid,” but don’t worry; it's not certain. Don’t worry, everyone; it’s not certain. There may only be a 20% chance that the body parts of your children will be scattered all over the wreckage. So, chop-chop, kids, get on board.

What parent does that? What functioning democratic state does that to 60 million people? Not one. No democratic state does that. Not ever does it. We could say that's common sense. We could say that's why the judge should not—and does not—have the final say. You, as ordinary people having heard what I've said, have the final say.

A tsunami of horrors, a tidal wave of terror—250 pages of evidence. You could say that we’re on the home stretch here then, couldn’t you? Certainly, the people listening to this after this trial will be thinking so. But this is a court of law, and we have to consider the law, don’t we? What does the law say about such a situation?

How do we find ourselves in 2024? It has been said that the law requires a close nexus between the action and the crime it intends to stop. It has to be close in time and space. No, it does not. What matters is causality—that the action stops the crime. A crime can be occurring now, or a crime can extend over years, over the whole world. It’s no less of a crime for distributing its murderousness over the whole of time and space—in this case, effectively into eternity.

That's nonsense, isn't it? No system of law can be stupid enough to suggest that there is a limit to the extent of a crime beyond which there can be no action that has a reasonable excuse. No action that tries to stop the harm. Obviously, the opposite is true. The greater the crime, the more you have a reasonable excuse to stop it.

It could be said that the law does not apply to new ways of killing people—that killing people by destroying their climate is not actually killing at all. It’s just, to quote the judge, “climate change,” a novel way of killing people, and thus not relevant in a British court. How ridiculous. How beyond stupid. Killing is killing. The novelty of the means of creating death is irrelevant. This is what any coherent system of justice has to demand.

And it has been said that we didn’t have to have no politics in the courtroom—that climate change “is a matter of personal belief”, of subjectivity. Well, let me say this: When I was at King’s College down the road, terrorists killed people at London Bridge. We all remember. And people tried to stop them. Were they told that this was wrong? Were they told that they were being political by trying to stop this extremism? Were the people that did the killing to be let off because they had a political motivation? No, no. No, no.

The question is: Was it killing or was it not? Many people who kill people have political beliefs, but that does not mean that they cannot be brought to trial, obviously. And the converse is true: Many people try to stop killing for political reasons. That does not mean that they don’t have a reason or excuse, obviously. Killing is killing; trying to stop it is not a crime. That’s common sense.

And lastly, we are required to attend to the legal consideration of whether our actions had an impact, had a real influence on the crime of emitting greenhouse gases.

Let me say this: I have studied the means of applying pressure. The means of applying pressure—I did research on this at King’s College for five years. I can tell you one thing: going onto a motorway is a standard and well-established way of getting attention, of creating pressure. It’s a standard mechanism to create success.

It was used by the farmers, remember, just a few weeks ago around Europe. Going on the roads, going on the motorways—the lorry drivers did it in the Blair government. As I said in my speech, the French, dare I say, do it all the time. The Serbian people did it two years ago to stop the loss of their mineral rights. It’s a thing; it works. We did it because it works—to stop a crime, a crime that we are all facing.

But let’s be honest with ourselves, please. Let’s be honest about this. Let’s not get lost in the reeds. The law is, first and foremost, one thing: protecting the welfare of the people. If it can’t do that, it’s nothing. We face what we face—the horror and the terror on a scale unknown in human history. Let’s get real. Let’s be honest, please. It’s common sense, isn’t it?

Any peaceful action that aims to stop killing, to stop the killing fields that are going to rain down on us, on our children, and the next thousand generations, has to be justified. Nothing, in fact, could be more justified.

I will finish by telling you why I did what I did—my personal reason for making that speech two years ago, asking people to take action. I did it for honour. To honour my mother. Honour is a value, isn’t it? But I suggest we re-adopt it as we face what is coming towards us. Honour your mother and your father. It used to be said.

My mother grew up in the Second World War. She knew the hardship and the stress of those times. Her generation knew what it was to face the reality of evil; they lived through it. The generation of that time fought evil, and they died for it.

My mother spent decades doing charity work. She was literally heartbroken by the suffering in this world. She told me when she was about to die that she would go into the bathroom, lock the door, and cry. Like millions of other Christian women, they dedicated their lives to the alleviation of suffering—the suffering of the innocent. This is what that generation did all around the world. They built a world that was more free, more prosperous, and more decent than any in human history. That was their legacy; that was their work, their light. They did it for us.

And I will not betray them. Over my dead body will I betray that legacy. I will not stand by and have everything destroyed on my watch. It is simply a question of honour. That is why I stand before you today.

So I have one request to make of you, members of the jury: that you yourself act in honour. New members of the jury, all of you in this courtroom, all of you who read about this speech after today, in the years ahead—because this is not about you, is it? It’s not about you. It’s about your family. It’s about your community. It’s about this country that we all love—you love and I love. It’s about honouring those that came before us and those that will come after us.

After everything I have told you, everything you know we now face, you have to act for love. As you members of the jury now know, if I stand before you and tell you this truth, I am put into prison. The lawyers in this trial, if they speak the truth, will lose their jobs.

If you speak the truth, nothing will happen to you. You are free to speak, and your freedom is burdened with great responsibility in this case—the greatest responsibility. I ask you to accept it: we had a reasonable excuse for doing what we did, for the love of the world, we did what we did.

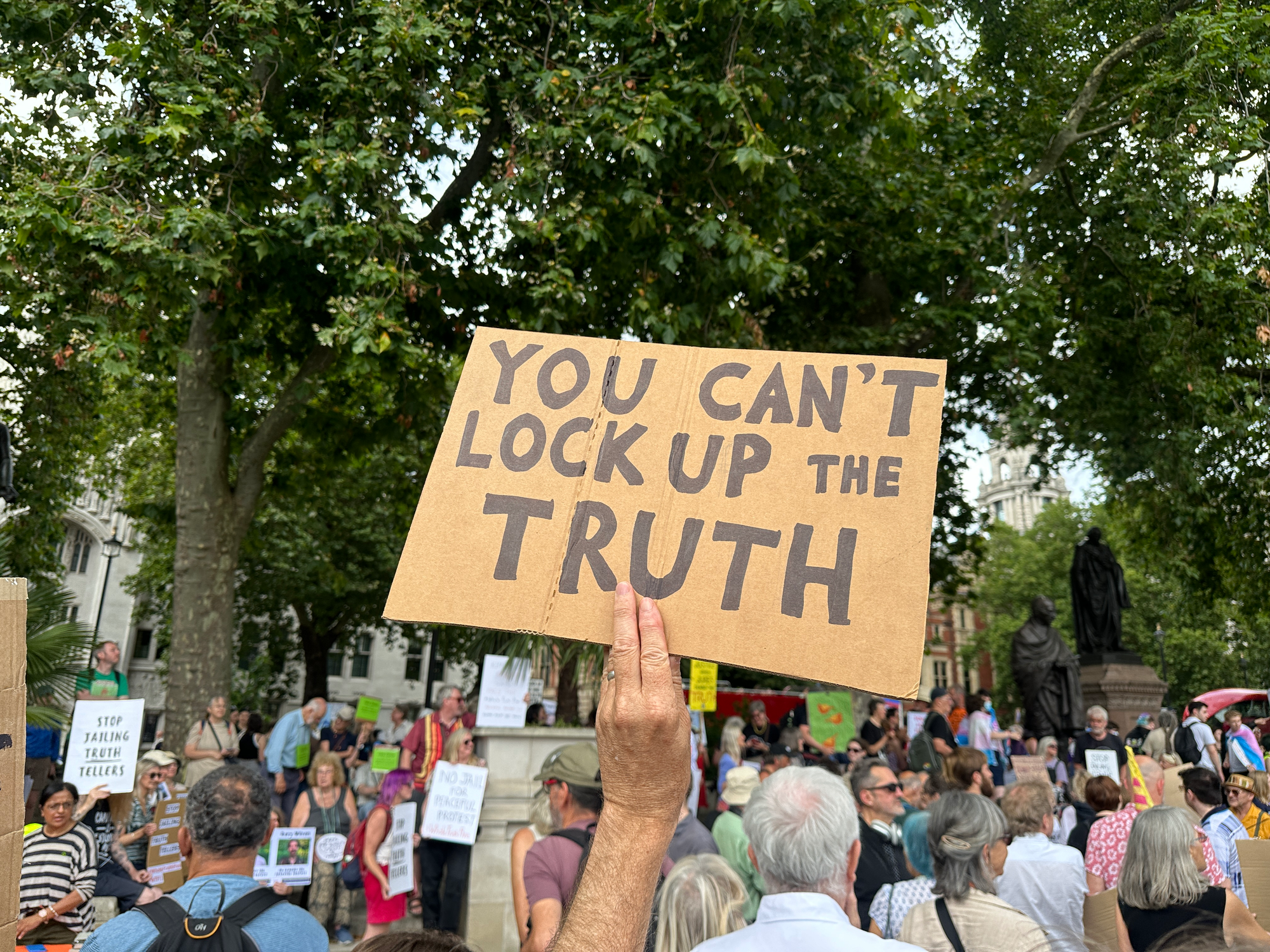

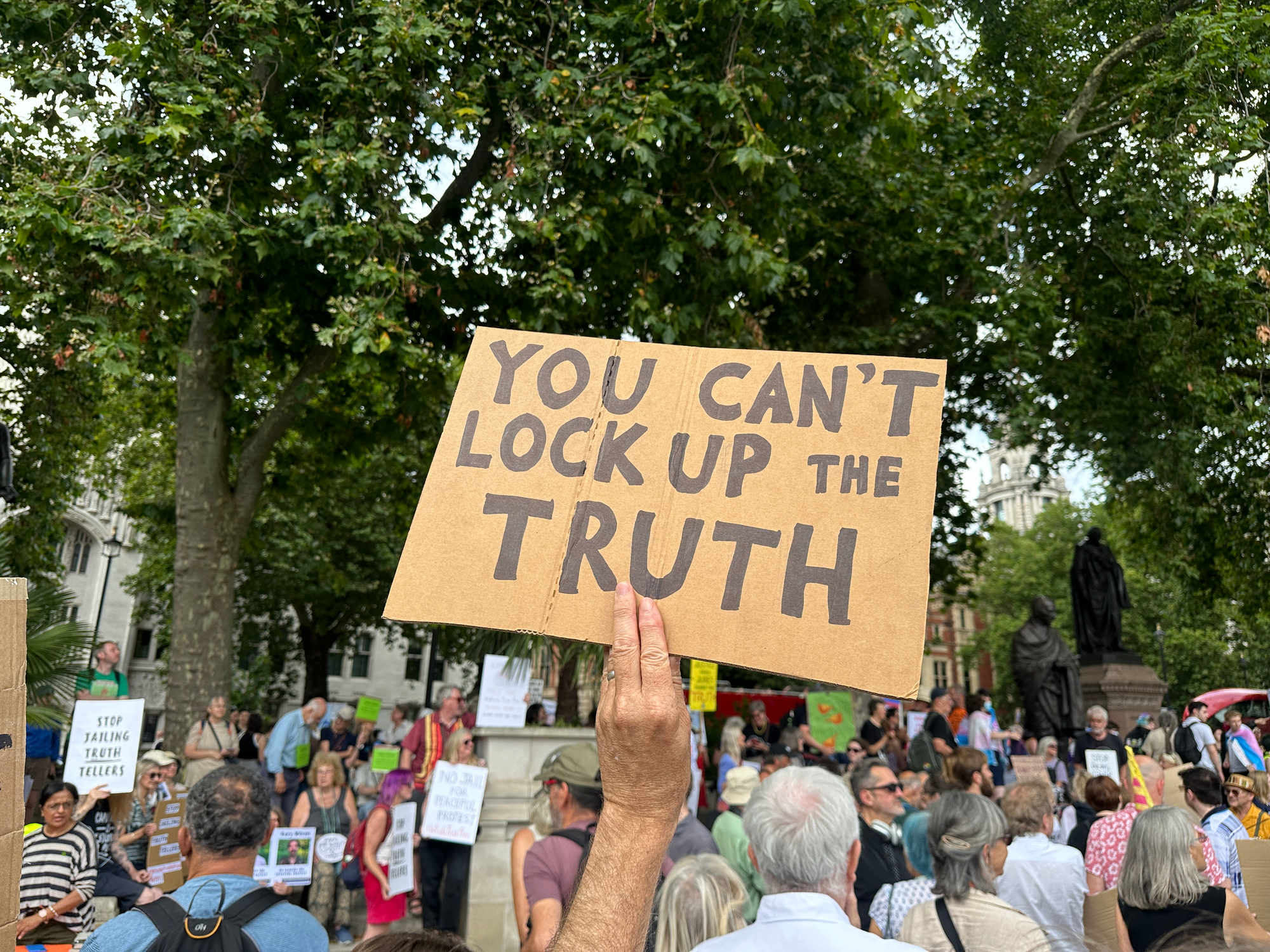

Thank you to everyone who joined our demonstration on Parliament Square to free imprisoned truthtellers. 60,000 have now signed a Petition to the new Attorney General to stop this madness. Please sign and share it.

If you'd like to send me a message of support, you can email a note through to me in prison by sending it to rogerremanded@gmail.com

As always, you can sign up for nonviolent civil resistance with Just Stop Oil in the UK or via the A22 Network internationally.