🙈 The Prison of Perception

In this episode, I’ll dive into how quantum physics and the very nature of consciousness force us to rethink everything we thought we knew about reality and time itself.

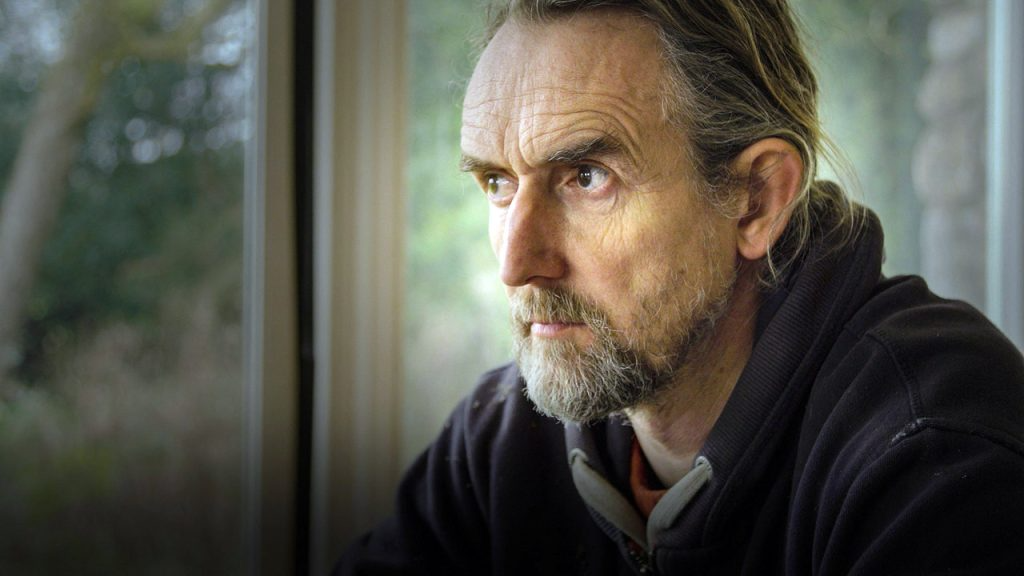

The relationship between the world, time, and us is mind-bending. I’m sitting at my table, in my cell, and pondering some deep questions. The table—this seemingly solid, real thing—actually raises a bigger question about what we’re truly seeing.

In this episode of The Spirit of Revolution, I will break down how the way we view reality, materialism, and even time itself might not be what we’ve been taught. We’re talking quantum physics, consciousness, and how our understanding of "stuff" could be all wrong. We’re not just sitting here; we’re shifting how we think about everything, and it’s leading us to some revolutionary ideas. Stay tuned, as we unravel these concepts and discover how the world, and even time, might not be as fixed as we once thought.

Listen on Spotify, Apple, Soundcloud or wherever you get your podcasts. We've worked to improve the prison phone sound quality and each episode will come with a transcript and video version on Youtube for reading along.

Transcript of Episode 4 - The World and Time

So let us return to the table business. Another day of writing, and yes, the table is in my cell. It's still here, solid and real—no problem there, except not so fast. As we just went through with the self, the notion of solid and real does not stand up to empirical observation. Empirics undermine the old realism, which is our central point here. The forced marriage which underpins the metaphysics of the materialist ideology breaks apart. Empirics point one way, and the old realism points in another way. This is the opening, the problematic, as you might call it. We are investigating to create the fluidity, the means to consider a new way of seeing.

The story with the table is well known in the world of science, but it is yet, yet to take off in wider culture, which is still captured by the premises—the false premises—of those 18th-century gentlemen. The questions go like this: So what is this real, solid table made of then? Wood? Okay, so what is the wood made of? Let's jump to atoms.

I remember, as a kid, feeling very pleased with myself that I'd sorted out that big question—what is the world made out of? Atoms, of course. Great, job done. Let's move on—except rationality demands that we can and should ask the question: So what are these atoms made of then? And observation provides an answer: we have electrons and protons, and then something weird happens. We go into quantum physics, where stuff (if you can call it that) appears out of nowhere and then disappears again, and where the act of observation affects what you see.

I don't pretend to be an expert in all this stuff, so I won't go on about it anymore. But obviously, there is something devastatingly subversive here. As a famous scientist once said, words to the effect: if you think you understand what is going on here, obviously you don't understand it. You can know—but only in a certain sense. That word again—sense. You have to get over the old, reductive, no-nonsense idea of there being "stuff" and then "no stuff." It turns out that if we think this, we are actually deluding ourselves. We are living in a pretend world in the same way as people who go, "I am myself." They can't or won't self-reflect.

We are stuck in a sort of prison—this idea of materialism, this idea that the world is just stuff. It's just plain wrong, according to scientific observation.

Whoops. So what does this have to do with anything? Well, the answer might be that if we can understand that stuff is not necessarily real, then we get this feeling of fluidity. I'm not knowing, at least for a moment—a little wobble, maybe. Maybe we don't have to have everything so tied down.

Let's look a little bit closer at this observer business. It's reasonably easy to go along with the "what is it made of" sequence of questions, even if we end up with the idea of stuff existing and not existing at the same time. But then there is the idea that the nature of stuff literally depends upon the act of you looking at it. This breaks down the dogma of another received thinking—that the observer and the observed are fundamentally separate. This seems to connect back to the previous section on the self—this idea of idealism, that the world is a function of the mind, but what we see depends upon how we see it.

The upshot is another hilariously transgressive idea—that the stuff in the world is, in fact, consciousness. Not actually so-called material stuff. Or, more radically still, this stuff is, in fact, just a form of consciousness. It turns out, according to science itself, that there is actually no stuff out there. There's only the mind looking at the mind. Consciousness—a wave, an energy, a flow, a world of all these things or approximate construction. It's all consciousness, baby.

This broad move, then, is that the world is not real—not in that facile, materialist sense—and this has massive implications. For a start, it makes scientists sound like old-style mystics. “This stuff exists, and yet it does not exist”. They start to speak the language of paradox rather than linear logic. You can gain knowledge not by resolving conceptions, but by encountering and experiencing them. The knowledge you gain is a sensibility rather than something solid and binary—exist or not exist, real or not real. There is something revolutionary here: the metaphysical basis of the project of extractive grasping possessiveness is found to be an imposed dogma. It's just plain wrong—getting more stuff going for growth; it's just a thing, a psychological hobby, a passing fad. The old mystics are back in town. It's all an illusion, according to observation.

Sociologically, then, this is bad news for the vast social superstructure that rests upon this old metaphysics. Fundamental ideas are essential to the maintenance of a regime—a system of action logic, as you might say. What I mean is the rationale for taking and holding material power. To cut to the chase: if stuff is not real, then why the hell spend all your life chasing after it?

There is what is called a cultural lag here. Once an ideational infrastructure starts to collapse—by which I mean a system of ideas—it can take a while for the broader cultural superstructure to get with the program. It's a bit like once the ideology of biological differences between human groups collapses; it can take decades for this to feed through into winning civil rights for black people and gay people. But it does feed through; it's effectively inevitable because fundamental dysfunctionalities in a social system cannot be sustained indefinitely. Something has to give.

And we can now add in the small additional point that chasing after stuff is actually destroying everybody's stuff—all stuff, the whole world, in fact. So it's only a matter of time before there's a big reckoning—more on this later, of course. So these are the social implications of all of this.

But let's return to ourselves, our sense of self, and our place in the world. The basic takeaway is: just as there is no atomized self, neither is there a solid, atomized world out there. The world is what we make of it, as you might say. Critically, this applies to being in a prison. I'm sitting here in this cell, or am I? It all depends on how you feel. In fact, there is no no-nonsense foundation to this world of stuff. There is not the world and then a bunch of subjective beliefs that some weird people have about it. It's not like, "Hey, Roger has a quaint belief about being in his cell." No, it is the idea that the very idea of this cell is itself subjective. It is, in fact, just an idea—one idea amongst others, a function of my consciousness.

Get a glimpse of this, and that this could be the case, and you can have a flash realization—an explosive sense of something, a sudden liberation, that moment of “aha!” Okay.

Remember, this cell is actually a bunch of waves and quarks and whatever else is moving in and out of consciousness, or at least that is as good an idea as the solid stuff idea. In realizing this, you are in fact in good company. Contrary to what we've been told, there are many wisdom and folk traditions that see the world in a similar way. It's just that we got removed from all of that by this big rationalist paradigm that's been shoved down our throats. What was not mechanical, binary, dead was seen just as personal belief, even as just superstitions. So it is easy to see how this opened up into a systematized industrial plunder, extraction, and rape.

Of course, there are lots of complications going on here, but this is where we're heading—towards a new top-level story for the next civilization. However, we are jumping ahead of ourselves. Let's come back to the table in this cell, to this locked cell. The minimum we can see is that things are not what they seem. The minimum we now know is that choice exists. There is an element of mystery, even a sense of awe introduced back into the physical world. There is an opening into another world, a re-enchantment, a joy of not being tied down to one way of seeing. In other words, the color starts to come back in when we look at the very small—quantum physics—and indeed the very large—the expanse of the universe. We get that strange feeling: there is self-evidently not just this set world here and now, but we're trapped in the splitting off of empiricism from the old realism. This opens up this new fluidity, as we have already identified.

And again, it is here that I am happy for us to stop for a while to find the fluidity and be with it, rather than rushing ahead and trying to get it all tied down again—neat and tidy, consistent and logical. I would suggest that being able to live with this fluidity, a sort of bottomless complexity, is another one of those muscles we have to develop to be true revolutionaries at the present time, at this moment in history. Because this enables us to give birth to what comes next.

We come back then to the language of transcendence—not just from the self, but from the world as well, from what we are and from what happens to us. We are in suspense because that is where we should be, rather than grasping onto some false foundation—the idolatry of the material—to bring us back to some old language. There is a functionality to thinking about the world in a material way. Of course, we are not throwing out the baby with the bathwater here; mechanics has its place. But that is precisely the point—it has a place; it is not the main show.

The main show is infinitely more mysterious than just this table, and so, time. Let's look at time, the self, the world, and now time. I must confess I have found the time the hardest nut to crack out of all of them. It seems so dominating, the iron hand remorselessly pulling you along. Time waits for no man; it's merciless with the self and the world. I've been fully engaged in their intrinsic ambiguities for a long time now—a joint assault of modern empirical science and traditional mysticism. That pincers movement has squashed the temporary humanist arrogance of the 18th-century rationalists. Sorry, guys, but time, of course, does not actually feel as it is according to the rationalists.

And that is the way it sometimes feels—like you can slow down, and sometimes it speeds up. For instance, the dull routine of prison makes the weeks fly by, as prisoners say the same thing day in, day out—the lack of anything new or unique happening. Then there is the power of perspective. When I was last in prison, I got a bit impressed with myself, and I said to another inmate, “Yeah, I'm in for six months.” Like, that was a long time. He said, “Well, yeah, I'm on my home stretch—only three more years.” I was properly put in my place, as you can imagine.

In this prison I'm in at the moment, along the corridor, it's all "lifers." One said to me, “So how long have you got?” “Five years,” I said. “Uh, that's not long,” he replied. “It's all about where we're anchored. If you're doing a 15-year stretch, well, during the last three, it's gonna feel like you're going home soon, right?” For people doing civil disobedience who are used to a month or two inside, three years can feel like an eternity. It's all perspective.

That then is a personal experience of time. At the other end of how you can see things, we have the objective data—the physics. It turns out that time is a thing, like everything else—everything, two words. You can bend it. In other words, it has characteristics; it can be changed. To be honest, again, I won't pretend I know all the ins and outs, but there is a bottom line here, an ultimate logic. Because time is just a thing; ultimately, it by definition is not totally set. It exists in the realm of things; it is therefore changeable.

It is not God. Consciousness, on the other hand, does seem to be everything, at least in a certain sense, in that it's through consciousness that everything comes into being. Without the mind, that conduit of consciousness, there can be nothing. This idea is supported by the findings in modern science that the universe is in fact consciousness. Again, you don't have to buy into this idea whole right now. You don't need to go, “Yeah, I agree,” or “I don't agree.” We can be in this zone where you sort of get it and sort of don't, and maybe you will, maybe you never will—our limited minds in the face of the divine.

We can be okay with that. And the exciting thing is that it's okay. Nice, if we can handle it, enables us to engage with the great myths and stories we have been told about time without having to follow that little voice in our head, rubbishing them all.

In particular, there are a few viewpoints I would like to briefly look at which throw everything into the air. Like, for instance, the view that there is only now—uh, now, like this moment now. You are listening to me or reading what I am communicating. Just focus on this nowness for a second: it's there, and then it's gone. You can come to the reasonableness of this idea by following the same sequence of questions we use to break down the notion of the atomized construction of the self. Like, where is the self? I cannot see it, so if I cannot see it, it can't exist—unlike this table here.

Similarly, you can ask, where is the past? You can ask, where is the future? Show me them. I mean, where are they? I'm an empiricist. I can see the table, but I cannot see the past. I cannot see where it is, so it doesn't exist, does it? Just more superstitious nonsense. The logic of empiric observation leads to a classical mystical declaration: there is only the now.

The variation on the theme is: there is only the now, but the future and the past, in a sense, still exist—they're just a function of the now. They're within the now; they only exist in this moment. There is the idea that history is the now imposed upon the past. The past can only exist through the perspective and context of the present.

All this is related to the idea that, therefore, time is forever a cycle, and all aspects of that cycle are contained within the present time. There is a predestination of endless repetition, for instance, the cycle of birth and death, growth and decay. This is all archetypal myth. There is no progress there, and as such, the circular replaces the linear.

As we have come on to investigate, it is possible to see ourselves as upon a stage. Life is enacted on this eternal stage, and we choose our role within it—how we respond to it. We are suddenly a long way from the factory clock. Once we allow some idea of consciousness to come out to the scene, the door's open to ideas of destiny and fate—the idea of some duty or responsibility to fulfill your destiny or to act out of fate. The whole world becomes reenchanted again. We have the adventure of will and choice. We have looked behind the veil of flat, linear, lifeless time to find something grand and glorious.

Consider also, for instance, the mystical and theological idea of end time. Time comes to an end. This is something physicists are thinking about—the investigation into the end of the universe. But within historical cultures, the notion is not just a scientific thing; it's drenched in drama. It is the final reckoning, the final judgment. This is a world of agency and thus responsibility. We are being held to account.

I would suggest that it has passed through not a few minds over the past decade what the destruction of the biosphere, the basis of life, means morally, theologically, mystically. The rationalist promised us Utopia, and instead, they brought us to this hubris. The end—is this a sick joke or what?

At the same time, there is a resistance to thinking about any of this. Don't even think about it, as the well-known book on the psychology of the crisis is called. And yet we are being drawn into this world of new understandings, not least because of the reality of the blatant betrayal, the false promise of those who told us how to think and act in that rational, conformist, linear way. And almost despite ourselves, we are drawn in, you might say. Because if we are to be saved, then it will be because we have a sense of agency again—a reason to act, a choice. This has to be preferable to being just another cog in the wheel of our elites' final death project, to being just a speck of dust in a meaningless dead universe.

You see, what the rationalist forgets is people actually like drama. You could say they like it more than happiness. That is why we're drawn to stories of drama. Our desire for some understanding of ourselves, this world, and time is all saturated in emotion. We are animated. We are alive. We were born to be this way.

So, some concluding thoughts: What I tried to show is that our worldview, our metaphysics, as I'm calling it, is not some dry academic thing restricted to university philosophy departments, all those unreadable books.

It is an alive, kicking thing. It's an emotional thing. The point is this: when someone comes up to you and says they're looking forward to going to prison for their resistance, and you can't believe it—you think they're making it up, they're being a dick—it's because it's you that are in a prison, not them. And your prison is worse because it's metaphysical. You carry it around every day, all your life, in your head: the prison of possessive individualism, possessive materialism.

I'm not saying this to try to get you to say, "Yeah, I agree, prison is great." What I am trying to get you to do is simply not to be shocked or surprised, and certainly not to be aggressive or mocking, but maybe to go, "Okay, yeah, I see what you mean." A bit like the poster: *Some people are gay, get over it.* Some people are okay going to prison, get over it. It's a matter of providing people with the dignity not to be embedded in the deep ideology of our dominant culture.

There are many ways to play the great game of life out there. The first step is to be open, to be curious and pluralistic. This process can be entered into via a number of paths or logics, lines of argument. What I have done in the last few episodes is use a scientific, logical investigation against itself—or at least against the ideology of our dominant culture—to expose a gaping, enormous contradiction at its core. That observation undermines the realest dogmas on the self, the world, and time. Atomistic stuff—they are not.

This is just one way into another world, but it is one way. We can learn to have less fear or even no fear. That is going to be our direction of travel. The reason you have fear of being in resistance and all its implications is not because—or just because—you lack the courage. In fact, that may not be the main reason at all. The main reason may be because you have allowed yourself to be locked into a very specific way of seeing. In the most basic sense, change that way of seeing—or rather, learn to be aware that there is another way of seeing—and suddenly you find yourself having the courage. The courage, in other words, is not created by you. It comes to you because the fear has gone, or rather, sometimes you find the fear is gone.

Going to prison can be just another day, and in a real sense, it is in fact just another day. So I hope we have made a small bridgehead into this new pluralism. We need to develop, deepen, and practice it; otherwise, we will fall back. It requires ongoing attention, and we will pay more attention in future episodes. I hope you are curious.

As always, you can sign up for nonviolent civil resistance with Just Stop Oil in the UK or via the A22 Network internationally.