What I Learned in Prison About Freedom

Civil resistance won’t succeed on material facts alone — faith, suffering, and humility might hold the key to revolution.

The following is an edited transcript of my second talk after release from prison. It takes place at How the Light Gets In, a philosophy festival in London. You can also watch the original recording or listen along on my podcast.

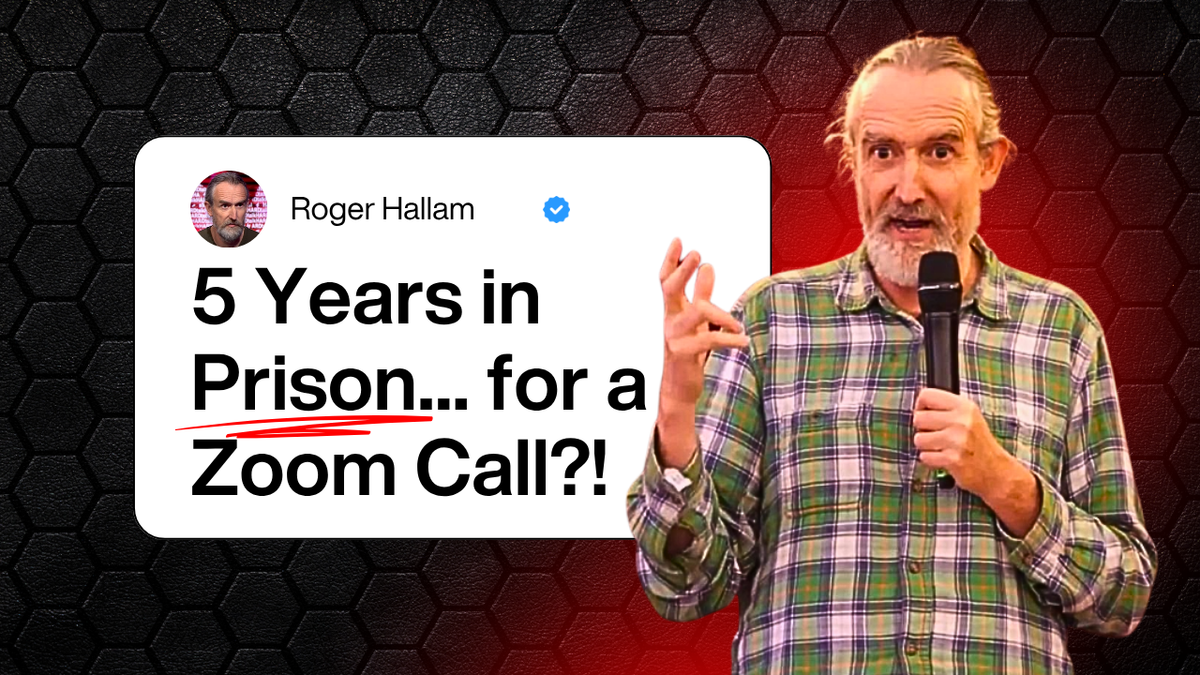

Last July, I was given a five-year prison sentence for being on a Zoom call asking people to take part in civil disobedience. It was later reduced on appeal — the judge called it “manifestly excessive” — so I served fourteen months, for better or worse. I was released in August. These days, I sleep in a hostel, with a tag on my ankle and all that sort of palaver.

That’s a bit of context, in case you’ve lost track. Many others have also been given multi-year sentences. It’s a new phenomenon in this country. In the so-called good old days, you’d get two weeks if you were unlucky — or lucky, as we’ll come on to.

I’m not going to talk much about politics. I want to talk about ideas — about how we construct the world, how we decide what’s good or bad. It’s a little philosophical, which is probably why I was invited here. And I’ll warn you now: none of this is original. It’s all been said before, by countless cultures through history. But that doesn’t make it any less true.

For the sake of having a point of focus, I’ve been re-reading The Imitation of Christ, a medieval Christian mystical text. Chapter twelve offers this line:

“It is good for us to encounter troubles and adversaries, for trouble compels us to search our hearts.”

That’s the thread I want to follow.

As a campaign designer, my work is about finding tipping points — the moments when enough people act that politics has to respond. If five hundred people in the UK were willing to go to prison for civil disobedience, we’d be in the realm of changing government policy. Maybe it’s two hundred, maybe it’s two thousand — but it’s not twenty thousand, and it’s not five. The point is, there’s a balance of power. When that balance shifts, change happens.

You can even do the maths. How many arrests before a government decides a policy isn’t worth the trouble? Five thousand, perhaps. We’re on around sixteen hundred now. That’s the kind of calculation campaigners like me make — not because we want people in prison, but because that’s what history shows moves the dial.

So what I’m really interested in is how we turn these personal experiences of hardship — trouble that compels us to search our hearts — into collective transformation. How we take that inner work and systematise it for the sake of saving something worth calling civilisation.

I’m not an academic; I’m a practitioner. I design campaigns. I work with people who want to act. So this is practical philosophy. It’s about how ordinary people, by facing trouble together, can still change the course of history.

Materialism

Let’s start with the materialist view — what you might call the modernist argument. It’s the one most of the climate movement uses. The basic line goes: it is what it is. There’s a world out there. Things are what they are. A table is a table. The thermometer reads what it reads.

Right now, the Earth is about 1.5°C above pre-industrial temperatures. That’s a fact, whether you like it or not. Temperatures are rising by roughly 0.3°C a decade, maybe 0.4°C as the acceleration bites. Do the maths and you hit 2°C within ten to fifteen years, depending on how you define the threshold.

From a realist perspective, that doesn’t look good. Once you hit 2°C, the best analysts predict around a billion refugees — a thousand million people on the move. The British insurance industry, ever the pragmatists, ran the numbers. They’re professional realists — if they get it wrong, they go bust. In true English fashion, they hid the shocking figures in an appendix rather than on the front page, because that would alarm people too much.

If you bother to look, Appendix A tells you that at 2°C we’re talking about two billion deaths, and at 3°C, four billion. And 2°C is only a decade or two away. So, if you weren’t already aware, we’re in a total mess.

Being a good liberal rationalist, the next logical step is action. If you believe the facts, you must act. That’s the foundation of the modern climate argument. And as a professional realist and campaign designer, I’d say: if you want to shift power, going to prison for civil disobedience is one of the few effective options left. There aren’t many others.

I’ve given over a hundred talks with this materialist framing. Around a quarter of people say they’ll take action afterwards, and maybe a fifth of those actually do. It’s not hopeless — it works on some. The problem is, it hasn’t done the job. It hasn’t reached the tipping point.

Why? Because not enough people take their materialism seriously. If they truly believed the facts they quote — that everything we love will disappear in the next twenty years unless we stop the fossil fuel industry — then they’d be acting as if their lives depended on it. Because they do.

But that’s where the modernist argument runs out of road. The facts alone aren’t enough to move people. And that’s why we need to look deeper — to the stories, meanings and beliefs that make people willing to act at all.

At five degrees, the human race, as a main scenario, goes extinct — because the phytoplankton in the oceans disappears. That’s what runaway climate change has done before in the Earth’s history: oxygen levels fall from around 25% to about 12%. You can’t breathe; we go extinct, along with most life on land.

So, if you’re a good materialist, it’s game over — which is precisely why you have to act. If the facts are that stark, you do what’s necessary, including prison if that’s what it takes. Before we move on, I’d simply invite you to notice the dissonance in your own mind — not judgmentally, more in a Buddhist way. I’m not here to tell you what to do, only to help examine the options. That’s materialism. Now, let’s look at postmodernism.

Postmodernism

Postmodernism covers a multitude of sins — art, culture, all the rest — but one useful strand is political postmodernism: the insistence that you can’t tell me who I am. Think of the progression with women, gay people, indigenous people. In the imperial modernist period, indigenous identity was criminalised and replaced with Western objectivism. Later came a patronising halfway house — you can be gay, but do it behind closed doors. Eventually, liberation arrives: two men holding hands is simply fine. That’s political postmodernism as a social progression.

What I want to add is metaphysical postmodernism, which hasn’t got very far. Here’s the provocation. Oscar Wilde spoke of “the love that dare not speak its name”. Now imagine I say: I love being in prison. The modernist reflex is outrage or indulgent correction: you can’t say that; prison is objectively bad. But a postmodern, metaphysical view allows plurality of experience. You might say I’m wrong; you might ban me from the festival. Or you might accept that, for some, the meaning of prison can be different — and that saying so is part of the point.

Fully fledged postmodernism is where I’m trying to get to — where I can come out as a prison lover. I like it and I’m proud. I’ve been to prison seven times. There’s a community of people who’ve been inside and secretly like it, but don’t feel permitted to say so. As more of us go, the secret seeps out: perhaps prison can be great — and I’ll explain why.

A quick example of patronising modernism. Novara Media (A left-wing news org in the UK) rang me in prison. “Roger, I’m so sorry you’re inside… how do you cope with prison?” It’s a loaded question. It assumes there is, objectively, something to cope with — like asking, “How do you cope with being gay?” I spent fifteen minutes trying to guide the journalist out of that materialist reflex the left is often trapped in — the absolutism of “objective” experience. This isn’t an abstract seminar point; it’s the raw reality of resistance and what it will mean.

Hence the title of this talk: On Being, in Prison. The emphasis matters. People ask, “What was it like being in prison?” The being is missing, as if only the locked door is real. But there’s prison — the door, the regime — and there’s being in prison: how being shows up within it. Culture conditions our panic. If this door were shut and locked for a while, would you necessarily have a crisis? Maybe, maybe not. One view says we’re little beings tossed about by circumstances, helpless. Another says the experience is dynamic; being is active even when the door is locked.

An example. On a previous stretch, I was in court every day. It’s a thirteen-hour day: three hours to get out, three back in, and you’re knackered. I returned one evening to find a new prisoner had been put in with my cellmate by mistake; they’d moved him on — and he’d nicked my stuff. I don’t have much, so what I do have is precious: your canteen bits, the small comforts that anchor you.

What little you have inside becomes precious — polos, canteen treats, the tiny stash in your cell. In prison you’re a bit like a twelve-year-old waiting for Canteen Day. After a thirteen-hour court day all you want is to sit with your polos — and they’re gone. A new lad had been mistakenly put in our cell and nicked my stuff. I told the officer; he said the bloke was a few doors down and he’d get it back. Half an hour later: nothing. Where could he have gone? It’s prison. I was furious — he’d taken my one little attachment to the world.

My cellmate laughed. He’s Buddha, been inside most of his life. Then I laughed too. Because everything can be taken from you except your being. That’s the lesson. Prison is a school for seeing that all you ever truly have is your being — here, now — not as some hippy slogan but as the actuality of living. You read this in your twenties during a mysticism phase and think it’s profound; you only really understand it after thirteen hours in court and your polos have vanished.

This is one instance of a universal phenomenon: adversity. Our modernist culture insists war or prison can only break you — PTSD, end of story. Yes, trauma is real. But if you’re being empirical, perhaps 10–20% of soldiers develop PTSD; far more report post-traumatic growth. After Vietnam, large studies found 60–70% said, twenty years on, that the experience was positive in the long arc of their lives. Not because war is “good”, but because suffering can be transfigured.

To be clear: I’m not claiming prison is good for everyone. People are broken by it; some never recover; some take their own lives. War destroys many. I’m arguing for plurality — a postmodern reading of experience. Alongside devastation there is, for many, growth. And that brings us back to The Imitation of Christ: it is good to encounter troubles and adversaries, for trouble compels us to search our hearts. That’s the point. Adversity strips away the props, and what remains — if anything remains — is being.

Bad things happening to you can be good, because they force you to search your heart.

That’s really all I’m asking you to consider: loosen up a little. Relax into a metaphysical postmodernism that admits the world is more complicated than materialist reductionism. Empirically, it just is. And then ask: what political function does that reductionism serve in maintaining the neoliberal regime? My proposition is simple: this is how the “bad guys” win — by persuading us that bad things are only bad.

My academic patch — insofar as I had one at King’s — was the psychology of mobilisation: how do you get people to act? Why do most people carry on for five years until the crisis lands in their lap, while perhaps ten per cent peel off and say, “Alright, I’m in”? In prison I caught up on the literature: twenty books on civil resistance. It’s mind-numbingly predictable. The pattern goes: everyone gets battered; then the religious currents arrive; then they win. Crude, yes, but look at the cases — the US civil rights movement (Southern Baptist church), Brazil’s landless workers (Catholic church), Leipzig 1989 (German Protestants), Solidarity in Poland (Catholicism), Iran (Islam), Gandhi in India, the Philippines in 1986 (again Catholic). I’m not selling Catholicism; I’m pointing to a through-line the secular texts reduce to “solidarity increased and then victory happened”.

What those accounts won’t ask — because it would break their metaphysical frame — is why faith communities so often tip the balance. They’d have to talk about the ontology of religious experience. And the answer isn’t mystical rocket science; it’s simply that the best ten days of your life may well be the ten days of the revolution. People love that moment — even when they might get shot. Not all, but most. Why? Because we aren’t just materialists. We seek meaning, recognition, transcendence. That’s not dogma; it’s observation.

This matters when we face what I call left defeatism. The materialist urban left churns out books with the same script: the world is bad; bad people are powerful; good people are crushed; if they resist, they’ll suffer; suffering is bad; therefore nothing can be done — and, behold, nothing happens. It’s a self-fulfilling neoliberal story. By insisting on an objectivist reading of suffering, the left disempowers people. It’s ideological nonsense — metaphysical nonsense — and you can hear it in a single word like cope. When that journalist asked, “How do you cope with prison?”, she couldn’t even see the frame she was imposing. That’s the culture we swim in — one that makes transcendence unsayable, and our destruction more likely.

If no one can transcend, we’re finished — that’s the direction of travel. So, the final act: religion. I can’t cover the whole thing in fifty minutes without being simplistic, ha — but my byline is simple enough: Glory be to God.

Religion

Three set-up points. First, people are fine with art but bridle at religion. Yet when you read “I wandered lonely as a cloud”, you don’t imagine Wordsworth literally dressed as cirrus. It’s a metaphor — a sensibility. Likewise, when I say Glory be to God, I’m not picturing a bloke in the sky being showered with petals. I’m pointing to an awareness of something beyond the table in front of us — what gets called “religious experience”, problematic phrase though it is.

Second, there’s a history to how religion was pushed out of public space. Before the Renaissance there wasn’t even a neat category called “religion”. The secular move did two things: fenced religion off from the rest of life, and privatised it — something you do on Sundays, not in public. Those are power moves that impose metaphysical modernism. Example: when the British went to India there was no word for “Hinduism” in the modern sense. Religion was woven through law, art, culture. We constructed “Hinduism” so we could declare, from above, “You are Hindus.” A projection of power.

From a postmodern view, that move is just that — a move. These constructions change. In a hundred years we’ll laugh at today’s modernists because the ambience of “religion” will have shifted again.

Third, on language. Part of my brain wants to say “spirituality” because “religion” feels hot. I’m resisting that. “Spirituality” has too often been neoliberalism’s trick: individualise faith into quietism. In the West, people say, “I’m not religious, I’m spiritual,” which often means a private little practice — yoga on Wednesday night — and then back to business as usual, planet included. I’m talking about religion woven through life: Mass on Sunday, feeding the homeless midweek, doing the law while thinking about God, speaking to your kids about it. Integrated, cultural, lived — though we’re discouraged from seeing it that way.

Given all that, it’s hard for us to grasp the empirical centrality of religious experience in shaping how we interpret the world. Hence half of you still think I’m a bit of a dick for saying prison is great — you’re caught in that paradigm. Yet in other times and cultures, when something “bad” happened, people knew it could also be good. Two quick examples. In Kenya, during the Mau Mau rebellion, capture and torture by the British was expected — fate, not melodrama. Likewise, when I go to prison for challenging the fossil fuel industry, of course they lock me up; that’s what power does. Or take the hill tribes in Burma during the Second World War: the Japanese invade, the men put on their war paint, women help, and no one collapses into a psychodrama. The cosmology is clear: you’re born, you grow, you fight for your people. What’s to cry about?

This is why the supposed objectivism of materialism doesn’t add up. Secular society talks to itself; out in the wider world, roughly 80% are “religious”. So, what would it mean to take religion seriously? We already know what taking someone seriously looks like: let them speak their reality in their own words. You don’t tell a gay person what being gay is like; you listen, language and swearing included. We’ve learned that with sexuality — two blokes holding hands barely rates a shrug now. But if I stood up and said a prayer in here, you’d twitch. That’s the gap. Taking religion seriously means giving it the same public legitimacy — the same right to speak — as anything else.

And no, I’m not claiming religion is automatically “good” — America has its fair share of right-wing zealots. My point is simpler: without a transcendent orientation, people don’t fight effectively. That lack of transcendence is why we’re losing.

So, how do religious people describe their experience? If I’m honest, the reason I like going to prison is straightforward: it brings me close to God. Bang. If you’re going to respect me, you let me say that in my own words. Meister Eckhart would say God is crying out — crying because you’re not close, because you’re ignoring suffering, because you won’t act in solidarity. When you do, you’re in communion.

For most of the world, that’s normal. I was chatting to a Seventh-day Adventist this morning — we could do God, no problem. The problem is the climate movement and secular activism can’t take that orientation seriously, which is why it’s still a love that cannot speak its name — though it’s starting to.

Here’s the kicker: prison doesn’t bring you close to God despite the shit; it does so because of the shit. Not for everyone, not all the time — I’m pleading for plurality in how we interpret “bad” events. And when people who are open to that experience come together, organise, and form a collectivity, you get successful civil resistance. Because civil resistance, at root, is driven by transcendence.

So I circle back. I was imprisoned for asking people to act, and I continue to ask it. The material case for action is overwhelming. The interpretive case is that suffering is not simply an evil to be avoided; it can be a crucible. The religious case is that, together, we can live by realities larger than fear. Successful civil resistance is driven by transcendence organised in common. Bring together those willing to be opened by adversity; give them a form and a fellowship; and you will find the tipping points of history again.

Everything can be taken from you apart from your being. Start there. Then act.

Rev21 Intro & Culture workshops |

Rev21 is gearing up for big collaborations – we're currently working with multiple groups and movements internationally to coordinate effective civil resistance, while refining and spreading best practices for cultural transformation. Come and experience how it feels to get inside this vision. Then get to know how we're going to make it happen, and find your way into making a meaningful contribution. |