🎤 Who Will Lead the Future? Planet Critical

A provocative clash of climate activism and philosophy: I argue that strategic non‑violence beats brute force—while questioning power, authority, and the very nature of self.

On this episode of Planet Critical, we discuss my theory of change, commitment to non-violence, and how to spark mass mobilisation. We frequently disagree, but have a detailed back-and-forth about these things. Enjoy on Rachel's site, wherever you get your podcasts, or as a condensed and tidy transcript below.

Rachel: Welcome to Planet Critical. It’s a pleasure to have you on the show.

Roger: Thank you.

Rachel: I’ve given you a big, long introduction for listeners who might not know who you are—our subscribers are from 186 countries around the world—so I’ll skip ahead a bit and bring us up to where you are now, recently out of prison, after what I think is a fair term to use: politically imprisoned. Since coming out, you’ve been writing about how you’re transitioning away from these campaigns of civil disobedience toward strategies of mobilisation and building a mass movement. Why the transition?

Roger: There’s a certain practicality to it. I got a five‑year sentence, which was then reduced to four years, meaning I’m on licence for another two years or so. If I promote civil disobedience—or engage in it—I’ll go back to prison, so on balance that’s not a good use of my time. The broader point is that, without sounding too dramatic, there’s a major shift in the climate‑left spaces toward a meta‑strategy—a big‑picture idea of creating social alliances in response to the rise of the far right. Everyone on the progressive left knows—or should know—that when the far right gets to power, they’ll do whatever it takes to implement far‑right policies, including scrapping the meagre climate action that exists today.

Everyone has their own issues and orientations, but everyone can come together because, regardless of values, those issues will disappear or be heavily challenged if the far right wins. I think we’ve moved out of what I’d call the neoliberal period, where people ran separate campaigns with weak ecological ties, toward a more mature political strategy where everyone works together on the two main issues: the far right and the power of the rich. Those two are obviously connected.

That strategy has two parts: an insider strategy and an outsider strategy—the optimal combination historically for changing regimes or resisting the far right. In other words, you run in elections, you build mutual‑aid systems, you build street movements, and bringing those forces together maximises the probability of success, rather than pursuing any one of them alone.

Rachel: So climate is no longer the umbrella? It’s now these two prongs—combating the right directly and targeting wealth inequality?

Roger: Many people think “wealth inequality” is a term constructed in the neoliberal period and highly politicised—something that becomes a technical, partial phenomenon open to reform. Those subliminal messages, every time you say “climate,” reinforce a particular view of political and social reality. The issue isn’t about climate per se; it’s about power relations in society.

When we set up Extinction Rebellion, we came from a non‑violent revolutionary background and wanted systemic change. Climate was one of several options and strategies. I argued that climate would be the battering ram—the word I used to force the unsustainability of the system politically, morally, and materially into the public sphere. That was the original idea of XR. But once we set up XR, many liberals moved into it, and it started to revert its framing back to climate as a partial issue open to reform, which was never the plan.

Rachel: Right, so the idea has always been systems change. With this strategic move toward mass mobilisation, we still need an entire systems change. I’m interested in the more traditional path—building political momentum, standing in elections, accessing the halls of power. How much can a system be changed from within? Once we’re in power, how restrictive will the opportunities be? Isn’t it true that we only ever see reform from within the halls of power, not revolution?

Roger: The main themes I’ll probably return to several times in this interview are that, in order to effectively change reality, we need to understand how reality works. So you have to step back and think about how we conceive political reality. Most people on the left are operating within a frame that was established during the Enlightenment—without getting too academic about it—but the buzzwords that float around are reductive, linear, materialist. What that basically means is that you view the world like a set of billiard balls: an election hits the election result, which hits getting into government, and then you hit a wall and can’t go any further. That’s simply not how it works.

As you know, we sort of understand this, yet we still revert to those bad habits of analysing why things worked the way they did. In reality everything affects everything all the time, which is quite difficult to operationalise. It’s a bit of a head‑fuck, conceptually. From an operational point of view, there are several “zones of outcomes” for actions, so you can’t reduce reality to a single concrete pathway.

What I mean is that when you engage in an election, you’re not just trying to win the vote. You’re also learning how to build a culture that can be used in different spheres of social activity—that’s one area. Another area is that you’re animating the social space: people get excited because there’s a radical option, like Zack Polanski’s at the moment. I’d call that social fluidity—people aren’t completely cynical; they have a bit of hope, and hope brings openness.

Then you have a baseline, a kind of social material, that can be developed into mutual‑aid networks and street movements. We have three “buckets.” The strategy, therefore, is to use the election to animate the social space, creating an inside‑outsider track rather than a reductive construction like “we’ll win thirty seats in the local election and then do A, B, C.” An election is still an election, with its own rationality, pros, and cons, as we all know. The point is that we need to be sophisticated about the meta‑aim: to animate and then shape the social space progressively through a series of iterations.

We mustn’t treat this as a static system. It’s not one thing banging into another while everything else stays the same. Everything is always changing and being reproduced, moment by moment. So my strategy is: we plan to do X, then Y, then Z, constantly iterating.

Rachel: Okay, but I’m hearing a few contradictions. You say things can’t be reduced, yet you also outline a chain—A leads to B leads to C—to animate the social space. That’s hugely important, and I agree that finding a collective common ground to build a political movement on is vital. However, I don’t think you’re taking into account the existing power dynamics that have consistently prevented, subverted, or co‑opted grassroots campaigns.

A good example is Podemos in Spain (2016). They won a minority and forced a coalition government, creating a moment that felt like a “pink tide” for Europe. Yet they quickly discovered how little you can achieve in government because of the interrelation of global financial systems, supply chains, trade rules, and EU membership. It’s actually quite hard to get things done, even if you can dramatically animate the social space—as Extinction Rebellion did, despite mixed public opinion.

That doesn’t necessarily translate into material change. Today, those in power—who hoard wealth—are willing to blatantly break international law and constitutional norms to protect their interests. We’re in a different historical moment, and that worries me. We can do a lot on the ground, but it may not translate into systemic change because the powerful have so much to lose and are unwilling to give any of it up.

Roger: There’s a balance between general principles and contextual analysis. On the left there’s a tendency to think in static terms—“if you do this, it won’t work”—but there’s never a universal “it won’t work.” It only fails in a particular time and space. Your analysis is historical; everything that is happening is technically in the past. So, when you talk about iterative design, a key understanding is that failure is part of the process toward success. You have to go through cycles of failure to build knowledge, culture, and resilience.

The real issue is how to fail in the best way rather than how to succeed. If you idealise success, you might do nothing because you think you won’t win. That’s the privileged viewpoint: “that won’t work because of A, B, C.” My reply is: what’s your plan? Any grounded strategy has to opt for the least‑worst option. There isn’t an “escape” from a privileged position; that’s a left‑defeatist narrative common in Western university culture—the notion of pure critique (“Oh, that won’t work”). Of course it won’t work perfectly, but it works better than all the other options. Sitting in a university writing papers is not a viable strategy.

Rachel: But… why? Why do you think it will work better than the alternatives?

Roger: Based on contextual analysis, first of all, and secondly, I’ve been in the game.

Rachel: What does “data‑based contextual analysis” mean?

Roger: It means that if we do X, then Y will happen in this context because it’s happened recently in the past. We’re constantly building up data on what can happen if we do A, B, C, so we can replicate successful patterns. Take Extinction Rebellion (XR) as an example. XR was a relative failure for the sake of argument, but it had elements that were really good. When we developed Just Stop Oil, we iterated on those elements—adding a proper leadership structure, which is essential in most contexts. Because that worked, we built a model that was good enough to launch the largest climate‑movement‑style actions in Italy, France, Germany, and Spain within twelve months.

It’s not purely probabilistic, but if you develop a model that substantially works, you can replicate it—at least across the Western world. Right now we’re trying to make that concrete: How can you use elections to win elections? By doing A, B, C you’ll win those elections, and you’ll also create concrete pathways to enhance mutual‑aid systems and street‑movement infrastructure.

For instance, I ran a stall on Saturday, got thirty people to join a WhatsApp group, three of whom turned up to a meeting, and two are now going to do door‑knocking or run a stall. I can mathematically work out the return on investment for a stall done a certain way. I spend a lot of time training people in micro‑designs—the key determinant of whether an iteration yields higher returns (i.e., more people get involved). It’s a challenging way of looking at things because many progressive leftists don’t view the world like this.

Rachel: No, it’s not difficult to understand. I just disagree with you. I also think you contradict yourself: earlier you said things aren’t static, that movements are always evolving, yet you claim that if we do A, B, C we’ll win an election—fundamentally reductive. Five minutes ago you said models are wrong but sometimes helpful; models are not predictive. How do you reconcile that?

Your original theory of change referenced Erica Chenoweth’s work on non‑violent resistance, suggesting that a small percentage (around 5 %) of the public needs to join a movement to create a tipping point. How has that held up? What have you learned from the climate movement that shows a mathematical, probabilistic approach is the best way forward?

You also said Just Stop Oil was “better” than Extinction Rebellion, which feels more qualitative than quantitative. While many chapters were started, public sentiment toward Just Stop Oil was more negative than toward XR (and the Palestine actions). I’m not blaming activists—the governments have responded harshly and jailed many unfairly. So I’m wondering: What do you define as “success,” and how do you measure it in your models? How does that confidence translate into the design approach you want to take moving forward?

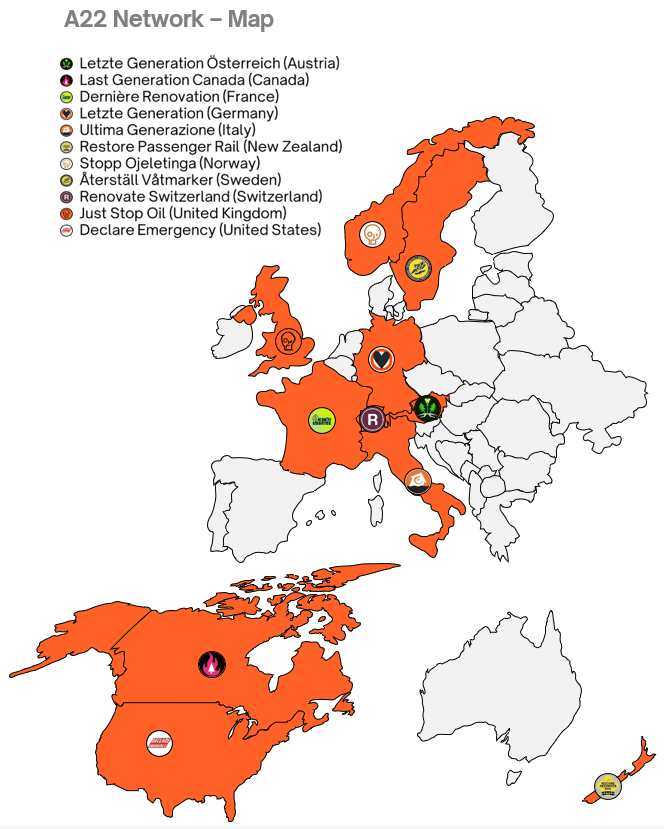

The A22 Network.

Roger: Well, as I said, the first thing to note is that you’re always designing—whether you decide to design or not. Everyone makes a decision about how to act, and in that sense you are always designing. So the question becomes how you design.

Design has an intuitive element, but there’s also an empirical, analytical, data‑driven side that helps—though it’s certainly not the only game in town. You’re right that a ratio (or model) is only as useful as long as the opposition doesn’t change their game. So, not being ultra‑reductive, but admittedly reductive because we all need to simplify reality to understand it, I’ll say this: It’s important to look at what you do and what the returns are. Put it in mathematical terms: if you run a stall in a certain way (A, B, C), you might get five sign‑ups an hour rather than two. That lets you create training modules—teach people that “if you do X, Y, Z you’ll get this outcome.” After you’ve tried ten or twelve different designs, you’ll be able to win an election in that particular space and time, obviously. That’s far more useful than not knowing how to act at all or acting in a way that simply doesn’t work in that context.

So, first: things are always changing—I totally accept that. Second: when I say something “works,” I don’t mean it necessarily changes the system in an ultimate sense. You’re right that Just Stop Oil was highly effective as an organisation and a mobilising force relative to XR, but it didn’t bring about a revolution; it failed to win over the public, and the government was able to crush it. I’m reasonably relaxed about that because, at a macro level, the game is: you do something, it fails, you try again, it fails less badly, and on the fourth iteration—especially given the system’s structural degeneration—you might have a fifty‑fifty chance of a pro‑social revolution in the next ten years. That requires fifteen years of preparation, cultural memory, and organisational continuity. Lack of memory is a huge problem because people simply don’t know what to do.

For us, messing around during local elections isn’t “messing around” at all; it’s part of a decade‑long meta‑project to work out how to transfer knowledge and ways of working—both internally and externally—so that when ruptures occur we can maximise the probability of scaling pro‑social forms rather than fascist ones. That’s the competition.

If you look at solidarity in the Polish resistance (1956‑1981), you see a pattern: they failed, then succeeded in 1981, failed again, and finally won properly in 1989. That’s the wave‑like history of radical politics—cycles of failure and resurgence.

Rachel: The reason I’m pushing you on this is that in one of your recent newsletters you wrote, “little projects with twenty people are useful, good, even beautiful, but they won’t stop fascism or meet the scale of what’s coming.” I was surprised because that sounds like you’re mandating one approach over another, which seems to remove agency from people, especially in rural areas. Perhaps those local projects are precisely what can build common ground, teach neighbours, and develop a collective political consciousness that feeds into a national super‑structure. My theory of change is that if everywhere had a small project with community workers, that could be the thing that stops fascism, rather than relying on a mainstream electoral party.

Roger: The nuance I’m trying to convey is that the binary—lots of tiny groups or one big group—is a false choice. What matters is the relationships between groups and how those relationships evolve over time. Think of it as a close ecology versus a loose ecology.

- In a close ecology, the flows of power, information, inspiration, and resources are intense.

- In a loose ecology, groups are isolated nodes that can be picked off by hostile forces.

Mass movements are necessary, but they shouldn’t be solid, Leninist‑style nodes. Instead, the mass movement must be built internally with a close‑ecology model. Many people haven’t heard that term because they default to a nineteenth‑century objectivist binary of “center vs. grassroots.” The real issue is the nature of the relationships and the flows among them.

Example: Neoliberal networking = meet once a month, share who you are, what you’re doing, why it’s “cool,” then disperse.

Close‑ecology networking = meet monthly, discuss what each group is doing, coordinate on funding, publicity, training, social events, etc. You create sub‑buckets where everyone coordinates. That moves beyond the binary.

So it’s not “small groups vs. big group”; it’s a network—a closed network where sovereignty resides in the coordination culture, not in individual nodes. That requires bureaucratic skills and cultural change: learning to trust each other, not sweating the small stuff, and adopting a “good‑enough‑to‑go” mindset. XR developed many of these practices so people don’t become dogmatic.

My tentative model for the UK: quarterly gatherings of everyone on the progressive left, with speakers, skill‑workshops, and at least half the agenda devoted to networking. For instance, a Sheffield event that brings together all local groups, then funnels energy into mutual aid, street movements, elections, etc.—essentially the pre‑1989 structure before the neoliberal period. While many historic structures were hierarchical and patriarchal, we don’t want to revert to that. The sweet spot for the 21st‑century left is individual identity retained, but everyone works closely together.

If you want an example of a successful close‑ecology, look at Mondragon—a cooperative economic model that could inspire a political analogue. The political sphere must fuse with the social sphere, and that’s what we’re aiming for.

Rachel: So projects should not be isolated from the surrounding action; otherwise they become vulnerable. I completely agree.

Roger: Exactly, and that needs to be concretised. Everyone talks about “building close ecologies,” but we need people in the field to actually create spaces where those ecologies can form, and to cultivate cultures of trust across nodes. That often means sharing identity and power across groups—something that clashes with the neoliberal legacy, which glorifies ego‑centric self‑interest (“I work hard, I succeed”).

Many legacy organisations won’t make that transition, and that’s not a criticism for its own sake; it’s an observation. We’ll likely need new organisations that embody these principles in most contexts.

Rachel: Okay. I have to say I’m a bit suspicious of anything that claims to want to build cultures for other people. I want to move away from mass movements and get onto non‑violence, which I’ve been looking forward to discussing with you.

You preach strict adherence to non‑violence and often cite Gandhi and MLK as emblematic success stories. In one of your recent newsletters you quoted Gandhi’s 1938 open letter to the Jews of Germany, where he suggested that their “voluntary suffering” could transform the Holocaust into a day of thanksgiving and blamed the Jews’ “inability to master non‑violence” for the massacre. You also wrote that Palestinian activism should abandon sabotage and adopt a concrete non‑violent strategy, saying that such a victory would matter beyond Britain and could show the world that civil resistance offers a way out of endless war. That stopped me in my tracks. It feels extraordinary for someone speaking from the comfort of Britain to tell Palestinians how they should fight for their lives. Can you walk me through what you were thinking with a statement like that?

Roger: Obviously you have to be quite brave to speak the truth. Speaking truth on various levels can get you killed or ostracised. I don’t say these things casually; I say them because, on balance, I’ll only be alive for another fifteen or twenty years at most, and I want to stay true to what I think I am—not a material being, but part of a universal consciousness. If I wanted a quiet life, I’d lie.

Rachel: All right, let’s attack that assumption—that it’s the truth. You say you’re doing it because it’s true and because some people have to be brave. The Palestinians have practised non‑violence; the recent “Great March of Return” saw thousands marching at the fence, with 218 people shot dead. It did nothing to help their cause; they were literally slaughtered.

Roger: Before I answer your question I need to finish explaining how I approach the situation, otherwise you and others will “do me in.” I need to say something first.

Rachel: Why? What do you mean “do me in”?

Roger: You’re making a moral criticism, accusing me implicitly of being privileged and therefore not knowing what’s best for Palestinians. Yes, I am privileged, but that doesn’t mean I can’t say things that are true, even if many Palestinians won’t agree with them.

Rachel: But just because something is true for you doesn’t make it objectively true.

Roger: I’ll come back to that in a minute. First, if we’re having a social‑scientific discussion we need to identify a prejudice embedded in patriarchal culture: killing another is acceptable, but allowing yourself to be killed is taboo. For example, an armed rebellion that kills two thousand people to overthrow a regime is often seen as “fair enough” because our culture accepts lethal sacrifice for a good cause. By contrast, if people sit on a road and 500 are shot, many view that as problematic, even if it achieves the same outcome. The prejudice is that “turning the other cheek” is aesthetically troubling, even though from a purely instrumental standpoint it’s just another death. If we treat all deaths as equal, the calculus changes.

We can agree that the cultural bias exists. You have two options: violent resistance that causes a thousand deaths, or non‑violent resistance that results in five hundred deaths but still works. You’d pick the lower‑death option, right?

Rachel: You’re pulling numbers out of thin air.

Roger: The point is that when you suggest people should die through non‑violence, people deem it problematic, whereas they don’t find it intrinsically problematic for the opposition to kill many in order to achieve their aims. That’s our cultural default, rooted in patriarchy: it’s okay to kill for a cause, but not okay to die for a cause. I’m arguing that the latter judgment is not inevitable.

Rachel: It’s an interesting point, and I recall reading it in one of your pieces. But I think the binary you present isn’t the whole story; there are many examples that complicate it.

Roger: It’s just a preamble. If we can agree on the cultural bias, we have a level playing field. Otherwise the debate collapses because each side just says, “I don’t like your method intrinsically.” That’s why the argument feels unwinnable for non‑violent advocates.

Rachel: Sure.

Roger: So if we accept the premise, we can move to the social‑science side.

Rachel: Hold on. Before we get into the social‑science, let me point out that there’s a global culture of self‑defence. Women, for instance, constantly practice self‑defence against sexual assault and domestic violence—forms of protection necessitated by patriarchy. It’s not just “men kill men.” Self‑defence strategies are sometimes absolutely necessary for survival, and they’re not confined to a male‑centric worldview.

Roger: I’ll come back to self‑defence in a minute. It depends on what you’re trying to do. You have an opposition—whether it’s a corporate entity, a state, or part of a regime—and you have two broad strategies: violent and non‑violent. The top‑level analysis, like the work of Erica Chenoweth and others, shows that non‑violence succeeds about 54 % of the time, while violence succeeds roughly 25 % of the time. That’s a static analysis, but it’s the best we have.

Rachel: Those figures have been challenged; the methodology has been questioned by other social scientists.

Roger: Everything gets challenged. The question is whether the challenges are substantive. In social science, a 54 % versus 25 % split, especially with a large sample size, is pretty robust. If the methodology were seriously flawed, we’d re‑evaluate, but the overall trend remains.

Rachel: Sure, but if the methodology is questionable, it’s not a done deal.

Roger: Agreed—if the data were unreliable, we’d need to reassess. As it stands, the evidence still points to non‑violence being statistically more effective overall.

Roger: You’ve got to develop a better methodology—something the critics haven’t offered. Looking at newspaper reports is “good enough” for many, but that’s misleading. I don’t think anyone is seriously questioning the methodology when there’s a degree of separation from the raw data. If the methodology were fundamentally flawed, that would be fine, but these are top‑tier social scientists. We have to give them credit for doing solid social‑science work. Assuming you believe in empirical investigation, those methods have been refined over several decades and are fairly robust. We don’t question climate science because of methodology—that would be a right‑wing, anti‑science stance.

Rachel: Social science isn’t the same as climate modelling. Chenoweth, for example, had to create categories for different forms of resistance, which introduces implicit bias. That makes her work different from something we can measure directly, and that’s where the criticism comes from. It’s a straw‑man to say the criticism is merely “right‑wing” when it actually targets methodological issues inherent to social science.

Roger: Yes.

Rachel: It’s valid to question the methodology.

Roger: My argument is that left‑critical culture is intrinsically fascistic because it defaults to violent solutions to human‑relations problems, especially at the state level. That bias, I think, will lead to extinction. We need a fundamentally different way of seeing reality. The “main case” isn’t the 54 % vs. 25 % statistic; it’s that in the 25 % of cases where violence wins, 95 % of those lead to civil war, loss of democracy, or social collapse within five years. A dynamic, long‑term analysis is required.

Take Cuba as an example: violence succeeded there, but five years later the country descended into authoritarian conflict. Violence, in itself, is fascistic. The real division for a pro‑social future is between violence and non‑violence—not between left and right. In the 21st century, the division should be between “othering” and “non‑othering.” That’s a philosophical/metaphysical point, but it’s supported by medium‑ to long‑term empirical evidence.

People who defend self‑defence and violence typically cherry‑pick examples and rely on static analyses. They ignore medium‑term outcomes. It’s like saying “I hit my wife; it worked,” ignoring that it destroys the relationship. We need to import the widely accepted cultures of non‑violence from interpersonal relations into politics. Politics isn’t fundamentally different from personal interactions. Fifty years ago, male violence against women was socially acceptable; today it’s not, reflecting a sea change in social attitudes. We need a comparable shift in the political sphere.

When violent situations arise (e.g., ICE raids), people revert to violence because their reasoning is instrumental, not metaphysical. That leads to cherry‑picking and short‑termism. Instead of saying “don’t hit a woman because it doesn’t work,” we should say “don’t hit a woman because it’s fundamentally wrong.” That’s the language we need when confronting violence.

Rachel: I agree that cultivating a non‑violent culture is crucial—it can set in motion changes that unfold over decades or centuries. What I’m pushing back against is the claim that non‑violence is the only strategy. Let’s look at West Papua. Are you familiar with that situation?

Roger: A little.

Rachel: There’s an ongoing genocide in West Papua. After the United States transferred control from the Dutch to Indonesia, Indonesia has imposed mass village loss, forced sterilisation of women, and widespread rape. West Papua is a biodiversity hotspot with massive gold and oil reserves. A guerrilla army of about thirty thousand Papuans is resisting a two‑million‑strong Indonesian military. Despite the disparity, they’ve survived for four‑five decades, employing brutal tactics such as forcing prisoners to dig their own graves and then shooting them.

Non‑violence requires a witnessing audience; without international attention, the Papuans have little chance of success.

Roger: This is the main theme for my upcoming book, How to Blow Up a Society (a response to Andreas Malm’s How to Blow Up a Pipeline). Guerrilla movements can endure for decades without taking power—think of insurgencies in Iran, India, the Philippines, various African nations. Longevity doesn’t guarantee victory. If you want to win, civil resistance typically succeeds within six to twelve months. Even when it wins, the resulting regime is authoritarian in roughly nineteen out of twenty cases.

Metaphysically, if someone doesn’t see you being non‑violent, it still matters because, over infinite time, the universe registers your actions. Good deeds, even unseen, eventually become known and amplify your impact. For me, non‑violence is a spiritual practice—doing it for God, as the old saying goes. Social science shows non‑violence is more effective, but it won’t persuade the most hardened opponents; most people aren’t purely rational.

The violent paradigm presents itself as a new religion based on love and acting for the good as an end in itself, arguing that love is instrumentally effective in complex systems. Some argue we need a quantum‑physics‑style politics rather than Newtonian—nothing is ever truly lost; everything affects everything. This resonates with Indigenous wisdom.

Our strategy, then, is to focus on who we are and what it means to be. In an egocentric, materialist worldview, fearing death and honoring the “other” as separate makes harming the other seem permissible. Recognising the other as essentially ourselves removes that justification. Violent people die, but they don’t see death as the issue; they see righteousness and efficacy as the issue. If we act as if the other is ourselves, we protect ourselves collectively. That would be my final statement on this.

Rachel: The thing is, that’s playing fast and loose with the “we.” First, indigenous wisdoms can’t be lumped into a single philosophy. The head of the freedom‑fighting army I interviewed in the jungle is an indigenous man, a devout Christian, who said his fight is justified because his path is right, just, and good. That belief sustains them against an army that vastly outnumbers them, and they fight not only for their own flesh but for their grandmother, the forest, and all the kin with whom they share land. Because the seat of power is overseas and they can’t leave, there’s no realistic route to winning an election and taking over. This has to be their fight.

It bothers me when Western intellectual “isms” try to speak for every lived experience. It’s imperative not to disparage strategies that keep people, communities, and languages alive. Different approaches work in different places. Some people might move toward non‑violence if given the opportunity, but not everyone has that opportunity. The idea that non‑violence alone can overthrow tyranny is problematic. Gandhi is often cited, but India today is not wholly non‑violent. The Partition saw hundreds of thousands of women raped; the caste system persists; industrialisation brought its own exploitation. Non‑violence didn’t produce a fully non‑violent society, and Gandhi’s specific tactics didn’t translate into a systemic shift.

Roger: Why wasn’t it non‑violent enough? You can argue the opposite, too.

Rachel: That’s easy, isn’t it?

Roger: It’s easy to point to a non‑violent act and say “still, things are bad.” That’s where professional social science shines: large‑scale, longitudinal analyses can trace causality. But most people aren’t persuaded by science. In my semi‑professional view, the patterns are clear—a “no‑brainer.” Strong social‑process patterns exist; they’re not random.

Rachel: So things can be reduced and are static?

Roger: The patterns are real.

Rachel: Then aren’t you cherry‑picking? Earlier you argued that nothing is static, everything relational, and now you claim fixed patterns that prove non‑violence always works.

Roger: Violence gives the highest probability of improving pro‑social dynamics, though it’s probabilistic, not deterministic. Practically, non‑violence works more often than violence—that’s the point.

Rachel: According to a methodology disputed by other social scientists.

Roger: It goes with the territory. I’m not interested in excessive post‑modernism; I favor a “dogma of love”: humans are part of a universal consciousness, and our role while alive is to love the other. That’s a simple doctrine I’m happy with.

Rachel: That sounds very much in the Enlightenment tradition.

Roger: Post‑modernism is a function of the Enlightenment. Fundamental quantum laws have been shown mathematically, yet I’m also comfortable treating this as an act of faith. Politically, I’m constrained by my day job, but my final volley—non‑violent, of course—is this intuition: Every act of violence carries a non‑trivial risk of escalation that could lead to extinction. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, the choice is non‑violence or non‑existence. Violence is a Russian‑roulette gamble with escalation. In the past, escalation led to revolutions or wars, but not an existential threat. Today, civil war in a major power could make extinction deterministic. We need a complete transformation of how we view ourselves and the other, based on love, God, and non‑violence. If that means someone dies, so be it, but death isn’t the end. Western fear of death is a driver of our potential extinction.

Rachel: I get you spiritually and metaphysically, and I agree with that sentiment. However, it doesn’t hold up for mothers fearing for their children, or for people whose lived realities differ. Erasing those experiences in the name of a “higher truth” can be cruel. This brings me to elitism in top‑down culture‑building. You wrote that in every historical period a small number of people carry the burden of design and organization. You call that reality, but it’s also elitism—centralized, hierarchical structures where a few decide for everyone. Indigenous sciences and politics emphasize decentralized decision‑making, sovereignty of the body, spirit, community, and land. If a tiny elite dictates global strategy, that mirrors existing power structures.

Roger: With respect, I reject the binary between “elitism” and “anti‑elitism.” We need fluid hierarchies and specialisations—people have different gifts and callings. Authority can arise from the bottom, not just the top (think of prophetic or spiritual leaders). Separating top‑down power from bottom‑up authority is crucial. Yes, a few people may know certain truths, but they don’t have to enforce them through patriarchal, top‑down models. Power itself isn’t inherently evil; it’s often boring and metaphysically empty. I’m not interested in holding power—my focus is creativity, flow, and inspiration. I set things up, stay for a couple of years, then step aside, having built a structure that can continue without me. This avoids the pathological effects of power on the psyche.

Rachel: Do you think you’re a prophet?

Roger: Unfortunately, I can’t give you a clear answer—I just get myself into trouble when I try.

Rachel: So you do.

Roger: Our culture is obsessed with power. If I said, “I’m a prophet,” people would call me an arrogant jerk. The problem is that our culture doesn’t recognize that some people have special gifts and can still be decent. Gandhi had a huge prophetic gift—courage and strategic leadership—but he wasn’t an asshole because he wasn’t interested in power. He wasn’t Stalin. If I say I’m a prophet, I’m just saying I wake up with ideas that motivate me, I go out and try to make them happen. If you call that “prophet” or label me a false prophet, that’s fine. It just shows how rigid we are about what it means to be human. Everything’s about power; Hobbesian thinking makes the world sad. We could relax a bit.

Rachel: But you distinguished between power and authority. You want authority even if you don’t want power, and you think you deserve authority. I’m asking you directly, Roger Hallam: do you want authority?

Roger: These issues will become more pressing as our metaphysics break down. One of our biggest prejudices is believing in “atoms” as discrete things—we’re so ingrained in that view we don’t even notice it. I see the universe and myself in a way most people don’t. I don’t even believe there is a persistent “self.” The “I” that speaks now disappears the moment I’m in another moment, and I just go on doing my thing.

Rachel: But you do exist, Roger Hallam, with a .com domain that calls you “the number‑one climate campaigner in the UK.” It feels like you’re using a “jail‑free card” by saying you can’t answer because you don’t know who you are. Do you want authority? Do you think you deserve it?

Roger: No, I don’t want authority at all. I just want to do what I think is right on a good day. That doesn’t mean I have no ego or no inner voice. I sometimes feel important because I’m on Planet Critical, but the real question is how aware I am of that voice. My intention is mostly to help make a better world. I didn’t set out to be famous. I was a farmer for twenty years, working 70 hours a week, earning £100 a week, raising kids, and living a simple life. I’m not interested in fame; I’m interested because the world is dying and I think I have some gifts to contribute. If I’m wrong, that’s fine. My trouble comes not from being an asshole but from insisting that two plus two equals four and refusing to deny it, even in a culture of chronic denial.

Rachel: I could argue that part of this conversation feels like denial on your part about different modes of being, different ways of interpreting research. You seem very certain about what must happen, which makes your arguments feel brittle and dismissive of the broader network of activity, ecosystems, and possibilities. You’ve spoken about needing networks, but I haven’t heard how you’re networking yourself into other things.

Roger: That’s a valid criticism; I’ll take it on board. Life is a constant struggle of nuance, isn’t it? I don’t wander around in perpetual self‑criticism. I still believe two plus two equals four, and I think killing is wrong. If someone calls me dogmatic, so be it.

You’ve got to live your belief, haven’t you? I try to remain open, but it’s obvious to judge whether I am. I’m living in an extreme crisis; important things need to happen. I’ve been thinking about this for fifty years and have a reasonable idea, even if I’m not perfect. I don’t have power in the sense of ordering people to be shot; I’m not Lenin. I’m not interested in running for office or leading a party. What interests me is enabling spaces to become empowered—much like organic farming, where you read the soil, not the plant. It’s a Daoist principle: the more power you have, the less effective you become.

My final question: who would you like to platform?

Roger: Michele Giuli in Italy—he’s one of the strongest voices in the movement right now. He founded a “Last Generation”‑type initiative and has robust arguments. I think he’d be great to talk to.

Rachel: Thank you very much for your time. I really appreciate it.